The world’s last wilderness areas are rapidly disappearing, with explicit international conservation targets critically needed, according to University of Queensland-led research.

The international team recently mapped intact ocean ecosystems, complementing a 2016 project charting remaining terrestrial wilderness.

Professor James Watson, from UQ’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, said the two studies provided the first full global picture of how little wilderness remains, and he was alarmed at the results.

“A century ago, only 15 per cent of the Earth’s surface was used by humans to grow crops and raise livestock,” he said.

“Today, more than 77 per cent of land—excluding Antarctica—and 87 per cent of the ocean has been modified by the direct effects of human activities.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

“It might be hard to believe, but between 1993 and 2009, an area of terrestrial wilderness larger than India—a staggering 3.3 million square kilometres—was lost to human settlement, farming, mining and other pressures.

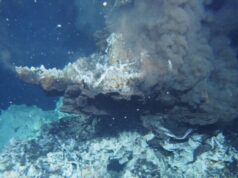

“And in the ocean, the only regions that are free of industrial fishing, pollution and shipping are almost completely confined to the polar regions.”

UQ Postdoctoral Research Fellow James R. Allan said the world’s remaining wilderness could only be protected if its importance was recognised in international policy.

“Some wilderness areas are protected under national legislation, but in most nations, these areas are not formally defined, mapped or protected,” he said.

“There is nothing to hold nations, industry, society or communities to account for long-term conservation.

“We need the immediate establishment of bold wilderness targets—specifically those aimed at conserving biodiversity, avoiding dangerous climate change and achieving sustainable development.”

The researchers insist that global policy needs to be translated into local action.

“One obvious intervention these nations can prioritise is establishing protected areas in ways that would slow the impacts of industrial activity on the larger landscape or seascape,” Professor Watson said.

“But we must also stop industrial development to protect indigenous livelihoods, create mechanisms that enable the private sector to protect wilderness, and push the expansion of regional fisheries management organisations.

“We have lost so much already, so we must grasp this opportunity to secure the last remaining wilderness before it disappears forever.”

The article has been published in Nature.

Provided by:

University of Queensland

More information:

James E. M. Watson et al. Protect the last of the wild. Nature (2018). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-018-07183-6

Image:

Torres Del Paine, Chile

Credit: Gregoire Dubois