Researchers at the University of Tübingen have shown that the shape of human teeth can be used to reconstruct genetic relationships. Dr. Hannes Rathmann and Dr. Hugo Reyes-Centeno of the University of Tübingen’s Humanities Center for Advanced Studies have established which specific dental features are best suited to infer genetic relationships and which dental features might instead reflect other factors, such as adaptations to the environment. The study has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Human tooth shape varies greatly among individuals and populations. Examples of common dental features include the groove patterns in crowns, the relative size of cusps, the number of roots, and the presence or absence of wisdom teeth. These dental traits are heritable, with certain traits commonly observed within families. Some of them occur at different frequencies across populations in a way that is similar to the inheritance and variation of DNA. “Dental traits can be used in population genetic studies when DNA is not available,” says Hannes Rathmann. Teeth are the hardest tissue in the human body and individuals’ dental remains are often well preserved, even when associated skeletal and DNA preservation is poor.

Neutral traits yield valuable information

“Most human dental traits probably arose by chance as a result of genetic drift,” Rathmann says. “That is an evolutionary process that is considered to be neutral, having no particular advantages or disadvantages for individuals or the population.” By contrast, it has also been proposed that some traits evolved in a non-neutral manner as a result of natural selection and adaptation, perhaps in response to chewing behavior or environmental factors. “Teeth that evolve neutrally are useful for inferring genetic relationships and can be highly informative for reconstructing the human past,” adds Hugo Reyes-Centeno. In order to disentangle the neutral and non-neutral evolutionary mechanisms, the researchers compared the variation in dental traits to the variation in neutrally evolving DNA across various populations around the world.

“For this study we developed an algorithm that could compare DNA data against commonly used dental traits and all the possible combinations of these traits,” explains Rathmann. The researchers performed extensive calculations and looked at more than 130 million possible combinations of dental traits. This enabled them to identify a set of highly informative trait combinations that preserve neutral genetic signals best—making them the most useful for reconstructing genetic relationships.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

Wide-ranging implications for forensic sciences, archaeology, and paleoanthropology

The findings could be applied in many different contexts, including the identification of unknown individuals in forensic cases, the investigation of mobility of ancient populations in archaeological studies, and the reconstruction of the origin and evolution of our species using human fossils in paleoanthropological research. “In such investigations, it may be that DNA cannot be retrieved due to poor preservation or when restrictions apply to destructive sampling,” says Reyes-Centeno. That is when dental traits become a very useful proxy for DNA. “We propose that future studies should prioritize the most effective dental traits and trait combinations found in our study, as they allow more accurate conclusions to be drawn about genetic relationships.” Including non-neutral dental traits could otherwise skew the results of the genetic analysis, the researchers say.

Provided by: Universitaet Tübingen

More information: Rathmann, et al. Testing the utility of dental morphological trait combinations for inferring human neutral genetic variation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914330117

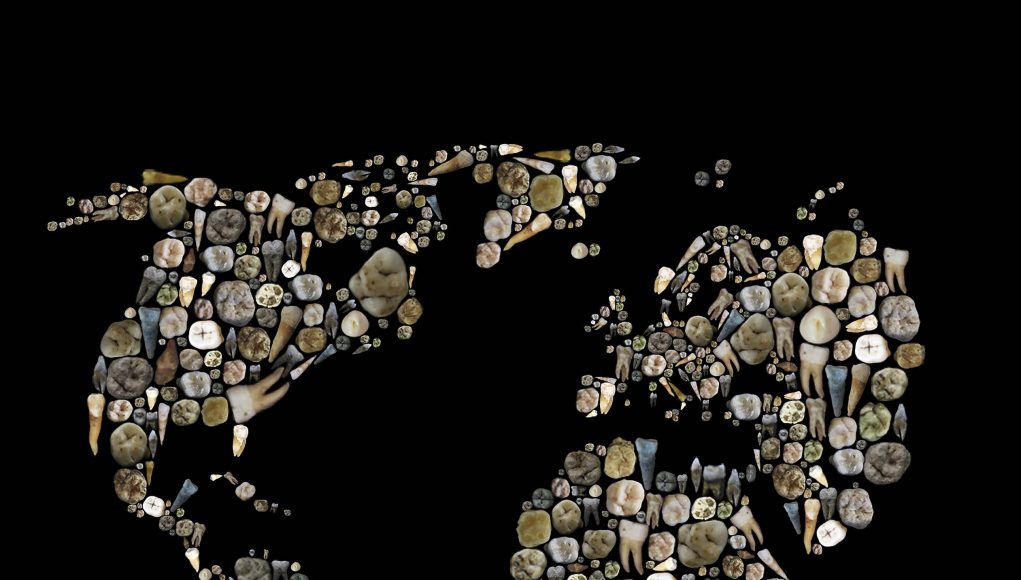

Image: A mosaic world map made from various human teeth. Photographs made at the Osteological Collection, University of Tübingen; graphic design: Peter Jammernegg (photographer and graphic designer).

Credit: Katerina Harvati/ University of Tübingen