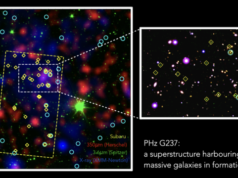

Comparison between the stellar (top) and molecular hydrogen (bottom) distribution in very gas-rich galaxies three billion years younger than the Milky Way. Optical data is from the Sloan Digital Survey whereas molecular hydrogen maps have been obtained using the Atacama Large Millimetre Array.

Credit: ICRAR

Astronomers have shed fresh light on the importance of hydrogen atoms in the birth of new stars.

Astrophysicist Dr Luca Cortese, from The University of Western Australian node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, said new stars are constantly forming in the Universe.

“New stars are born in dense clouds of gas and dust that are found in most galaxies,” he said.

“Our own Milky Way forms about one new star a year on average.”

In the local Universe close to us about 70 per cent of the hydrogen gas is found in individual atoms, while the rest is in molecules.

Astronomers had expected that as they looked back in time, younger galaxies would contain more and more molecular hydrogen until it dominated the gas in the galaxy. Instead, they found that atomic hydrogen makes up the majority of gas in younger galaxies too.

This is true even in galaxies under conditions similar to ‘cosmic noon’, a period about seven billion years after the Big Bang when the rate of star formation in the Universe reached its peak.

Dr Cortese said that in the last decade astronomers have discovered young, star-forming galaxies at cosmic noon with 10 times more hydrogen molecules than the Milky Way.

With such large reservoirs of molecular hydrogen, no room seemed to be left for a comparable amount of cold atomic gas. Unfortunately, it is currently impossible to detect hydrogen atoms at such large distances and verify this expectation.

Instead, Dr Cortese and his team discovered a population of galaxies three billion years younger than the Milky Way hosting gas reservoirs at least as large as those of galaxies at the cosmic noon.

“What we found is that despite hosting 10 billion solar masses of molecular gas these young galaxies turn out to be very, very rich in atomic hydrogen as well,” Dr Cortese said.

“The balance between atomic and molecular hydrogen is pretty much the same as in the Milky Way. In other words, it’s still dominated by atomic gas.”

The research used data from two of the world’s most powerful radio telescopes, the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and the European Southern Observatory’s Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile.

ICRAR astrophysicist Dr Barbara Catinella, who was a co-author on the research, said the findings have tremendous implications for our understanding of the early Universe.

“It shows that we cannot neglect atomic hydrogen even in galaxies that contain tens of billions of solar masses of molecular hydrogen,” she said.

“Only the advent of future radio telescopes such as the Square Kilometre Array will allow us to get a complete picture of the role of cold gas in the star formation cycle.”

A further finding from the study is that the galaxies rich in molecular hydrogen were not very turbulent.

Usually, these galaxies would be expected to be very turbulent to prevent the collapse of the gas into stars.

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Story Source: Materials provided by International Centre for Radio Astronomy Researc Original written by Whitney Clavin.Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

L. Cortese, B. Catinella, S. Janowiecki. ALMA Shows that Gas Reservoirs of Star-forming Disks over the Past 3 Billion Years Are Not Predominantly Molecular. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, October 2017