Based on data from NASA’s K2 mission, an international team of scientists has confirmed nearly 100 new exoplanets. This brings the total number of new exoplanets found with the K2 mission up to almost 300.

“We started out analyzing 275 candidates of which 149 were validated as real exoplanets. In turn 95 of these planets have proved to be new discoveries,” said American PhD student Andrew Mayo at the National Space Institute (DTU Space) at the Technical University of Denmark.

“This research has been underway since the first K2 data release in 2014.”

Mayo is the main author of the work being presented in the Astronomical Journal.

The research has been conducted partly as a senior project during his undergraduate studies at Harvard College. It has also involved a team of international colleagues from institutions such as NASA, Caltech, UC Berkeley, the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Tokyo.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

The Kepler spacecraft was launched in 2009 to hunt for exoplanets in a single patch of sky, but in 2013 a mechanical failure crippled the telescope. However, astronomers and engineers devised a way to repurpose and save the space telescope by changing its field of view periodically. This solution paved the way for the follow up K2 mission, which is still ongoing as the spacecraft searches for exoplanet transits.

These transits can be found by registering dips in light caused by the shadow of an exoplanet as it crosses in front of its host star. These dips are indications of exoplanets which must then be examined much closer in order to validate the candidates that are actually exoplanets.

The field of exoplanets is relatively young. The first planet orbiting a star similar to our own Sun was detected only in 1995. Today some 3,600 exoplanets have been found, ranging from rocky Earth-sized planets to large gas giants like Jupiter.

It’s difficult work to distinguish which signals are actually coming from exoplanets. Mayo and his colleagues analyzed hundreds of signals of potential exoplanets thoroughly to determine which signals were created by exoplanets and which were caused by other sources.

“We found that some of the signals were caused by multiple star systems or noise from the spacecraft. But we also detected planets that range from sub Earth-sized to the size of Jupiter and larger,” said Mayo.

One of the planets detected was orbiting a very bright star.

“We validated a planet on a 10 day orbit around a star called HD 212657, which is now the brightest star found by either the Kepler or K2 missions to host a validated planet. Planets around bright stars are important because astronomers can learn a lot about them from ground-based observatories,” said Mayo.

“Exoplanets are a very exciting field of space science. As more planets are discovered, astronomers will develop a much better picture of the nature of exoplanets which in turn will allow us to place our own solar system into a galactic context”.

The Kepler space telescope has made huge contributions to the field of exoplanets both in its original mission and its successor K2 mission. So far these missions have provided over 5,100 exoplanet candidates that can now be examined more closely.

With new, upcoming space missions like the James Webb Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, astronomers will take exciting new steps toward characterizing and studying exoplanets like the rocky, habitable, Earth-sized planets that might be capable of supporting life.

Provided by:

Technical University of Denmark

More information:

Andrew W. Mayo et al. 275 candidates and 149 validated planets orbiting bright stars in K2 campaigns 0-10. Astronomical Journal, 2018 DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/aaadff

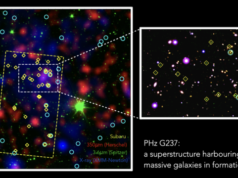

Image:

After detecting the first exoplanets in the 1990s it has become clear that planets around other stars are the rule rather than the exception and there are likely hundreds of billions of exoplanets in the Milky Way alone. The search for these planets is now a large field of astronomy.

Credit: ESA/Hubble/ESO/M. Kornmesser