Scientists have tracked a ‘boomerang’ earthquake in the ocean for the first time, providing clues about how they could cause devastation on land.

Earthquakes occur when rocks suddenly break on a fault—a boundary between two blocks or plates. During large earthquakes, the breaking of rock can spread down the fault line. Now, an international team of researchers have recorded a ‘boomerang’ earthquake, where the rupture initially spreads away from initial break but then turns and runs back the other way at higher speeds.

The strength and duration of rupture along a fault influences the among of ground shaking on the surface, which can damage buildings or create tsunamis. Ultimately, knowing the mechanisms of how faults rupture and the physics involved will help researchers make better models and predictions of future earthquakes, and could inform earthquake early-warning systems.

The team, led by scientists from the University of Southampton and Imperial College London, report their results today in Nature Geoscience.

While large (magnitude 7 or higher) earthquakes occur on land and have been measured by nearby networks of monitors (seismometers), these earthquakes often trigger movement along complex networks of faults, like a series of dominoes. This makes it difficult to track the underlying mechanisms of how this ‘seismic slip’ occurs.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

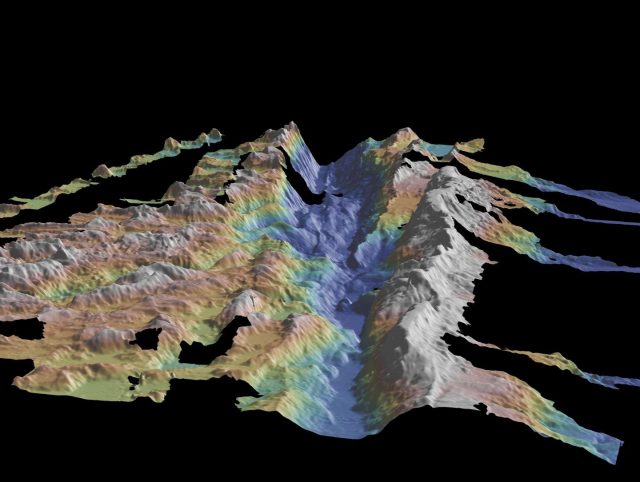

Under the ocean, many types of fault have simple shapes, so provide the possibility get under the bonnet of the ‘earthquake engine’. However, they are far from large networks of seismometers on land. The team made use of a new network of underwater seismometers to monitor the Romanche fracture zone, a fault line stretching 900km under the Atlantic near the equator.

In 2016, they recorded a magnitude 7.1 earthquake along the Romanche fracture zone and tracked the rupture along the fault. This revealed that initially the rupture traveled in one direction before turning around midway through the earthquake and breaking the ‘seismic sound barrier’, becoming an ultra-fast earthquake.

Only a handful of such earthquakes have been recorded globally. The team believe that the first phase of the rupture was crucial in causing the second, rapidly slipping phase.

First author of the study Dr. Stephen Hicks, from the Department of Earth Sciences and Engineering at Imperial, said: “Whilst scientists have found that such a reversing rupture mechanism is possible from theoretical models, our new study provides some of the clearest evidence for this enigmatic mechanism occurring in a real fault.

“Even though the fault structure seems simple, the way the earthquake grew was not, and this was completely opposite to how we expected the earthquake to look before we started to analyze the data.”

However, the team say that if similar types of reversing or boomerang earthquakes can occur on land, a seismic rupture turning around mid-way through an earthquake could dramatically affect the amount of ground shaking caused.

Given the lack of observational evidence before now, this mechanism has been unaccounted for in earthquake scenario modeling and assessments of the hazards from such earthquakes. The detailed tracking of the boomerang earthquake could allow researchers to find similar patterns in other earthquakes and to add new scenarios into their modeling and improve earthquake impact forecasts.

The ocean bottom seismometer network used was part of the PI-LAB and EUROLAB projects, a million-dollar experiment funded by the Natural Environment Research Council in the UK, the European Research Council, and the National Science Foundation in the US.

More information: Stephen P. Hicks et al. Back-propagating supershear rupture in the 2016 Mw 7.1 Romanche transform fault earthquake. Nature Geoscience (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-020-0619-9

Image: Reconstructed image of the fracture zone.

Credit: Hicks et al