There may be more habitable planets in the universe than we previously thought, according to Penn State geoscientists, who suggest that plate tectonics—long assumed to be a requirement for suitable conditions for life—are in fact not necessary.

When searching for habitable planets or life on other planets, scientists look for biosignatures of atmospheric carbon dioxide. On Earth, atmospheric carbon dioxide increases surface heat through the greenhouse effect. Carbon also cycles to the subsurface and back to the atmosphere through natural processes.

“Volcanism releases gases into the atmosphere, and then through weathering, carbon dioxide is pulled from the atmosphere and sequestered into surface rocks and sediment,” said Bradford Foley, assistant professor of geosciences. “Balancing those two processes keeps carbon dioxide at a certain level in the atmosphere, which is really important for whether the climate stays temperate and suitable for life.”

Most of Earth’s volcanoes are found at the border of tectonic plates, which is one reason scientists believed they were necessary for life. Subduction, in which one plate is pushed deeper into the subsurface by a colliding plate, can also aid in carbon cycling by pushing carbon into the mantle.

Planets without tectonic plates are known as stagnant lid planets. On these planets, the crust is one giant, spherical plate floating on mantle, rather than separate pieces. These are thought to be more widespread than planets with plate tectonics. In fact, Earth is the only planet with confirmed tectonic plates.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

Foley and Andrew Smye, assistant professor of geosciences, created a computer model of the lifecycle of a planet. They looked at how much heat its climate could retain based on its initial heat budget, or the amount of heat and heat-producing elements present when a planet forms. Some elements produce heat when they decay. On Earth, decaying uranium produces thorium and heat, and decaying thorium produces potassium and heat.

After running hundreds of simulations to vary a planet’s size and chemical composition, the researchers found that stagnant lid planets can sustain conditions for liquid water for billions of years. At the highest extreme, they could sustain life for up to 4 billion years, roughly Earth’s life span to date.

“You still have volcanism on stagnant lid planets, but it’s much shorter lived than on planets with plate tectonics because there isn’t as much cycling,” said Smye. “Volcanoes result in a succession of lava flows, which are buried like layers of a cake over time. Rocks and sediment heat up more the deeper they are buried.”

The researchers found that at high enough heat and pressure, carbon dioxide gas can escape from rocks and make its way to the surface, a process known as degassing. On Earth, Smye said, the same process occurs with water in subduction fault zones.

This degassing process increases based on what types and quantities of heat-producing elements are present in a planet up to a certain point, said Foley.

“There’s a sweet spot range where a planet is releasing enough carbon dioxide to keep the planet from freezing over, but not so much that the weathering can’t pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and keep the climate temperate,” he said.

According to the researchers’ model, the presence and amount of heat-producing elements were far better indicators for a planet’s potential to sustain life.

“One interesting take-home point of this study is that the initial composition or size of a planet is important in setting the trajectory for habitability,” said Smye. “The future fate of a planet is set from the outset of its birth.”

The researchers published their findings in the current issue of Astrobiology.

Provided by:

Pennsylvania State University

More information:

Bradford J. Foley, Andrew J. Smye. Carbon Cycling and Habitability of Earth-Sized Stagnant Lid Planets. Astrobiology (2018). DOI: 10.1089/ast.2017.1695

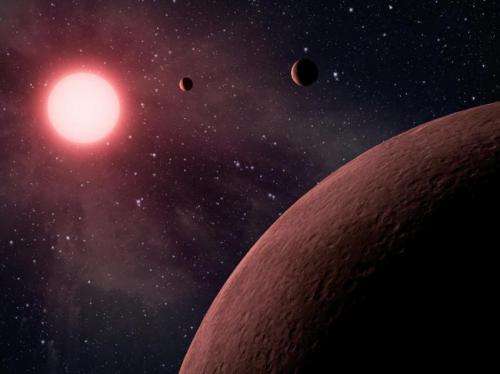

Image:

This artist’s concept depicts a planetary system. Credit:

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech