Listening to electromagnetic waves around the Earth, converted to sound, is almost like listening to singing and chirping birds at dawn with a crackling campfire nearby. Such waves are therefore called chorus waves. They cause the Northern Lights, but also high-energy ‘killer’ electrons that can damage spacecraft. In a recent study to be published in Nature Communications, the authors describe extraordinary chorus waves around other planets in our solar system.

The scientists led by Yuri Shprits of GFZ and the University of Potsdam report that the power of chorus waves is 1 million times more intense near the Jovian moon Ganymede, and 100 times more intense near the moon Europa than the average around these planets. These are the new results from a systematic study on Jupiter’s wave environment taken from the Galileo spacecraft.

“It’s a really surprising and puzzling observation showing that a moon with a magnetic field can create such a tremendous intensification in the power of waves,” says the lead author of the study, Professor Yuri Shprits of GFZ/ University of Potsdam, who is also affiliated with UCLA.

Chorus waves are a special type of radio wave occurring at very low frequencies. Unlike the Earth, Ganymede and Europa orbit inside the giant magnetic field of Jupiter, and the authors believe this is one of the key factors powering the waves. Jupiter’s magnetic field is the largest in the solar system, and some 20,000 times stronger than the Earth’s.

“Chorus waves have been detected in space around the Earth, but they are nowhere near as strong as the waves at Jupiter,” says Professor Richard Horne of British Antarctic Survey, a co-author on the study. “Even if small portion of these waves escapes the immediate vicinity of Ganymede, they will be capable of accelerating particles to very high energies and ultimately producing very fast electrons inside Jupiter’s magnetic field.”

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

Jupiter’s moon Ganymede was first found to have a magnetic field by Professor Margaret Kivelson and her team at the University of California, Los Angeles, and strong plasma waves were first observed near Ganymede by Professor Don Gurnett and his team at the University of Iowa. However, until now, it remained unclear if this was accidental or whether such increases are systematic and significant.

Around Earth, chorus waves play a major role in producing high-energy ‘killer’ electrons that can damage spacecraft. The new observations raise the question as to whether they can do the same at Jupiter.

Observations of Jupiter’s waves provides a unique opportunity to understand the fundamental processes that are relevant to laboratory plasmas and the quest for new energy sources, and processes of acceleration and loss around the planets in the solar system. Similar processes may occur in exoplanets orbiting other stars, and the findings of this study may help to detect whether exoplanets have magnetic fields by providing very important observational constraints for theoretical studies to quantify the increase in wave power.

Provided by:

Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

More information:

Y. Y. Shprits et al. Strong whistler mode waves observed in the vicinity of Jupiter’s moons. Nature Communications (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05431-x

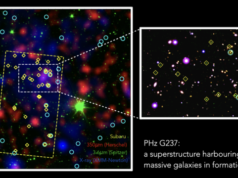

Image:

This natural color view of Ganymede was taken from the Galileo spacecraft during its first encounter with the Jovian moon. North is to the top of the picture and the sun illuminates the surface from the right. The dark areas are the older, more heavily cratered regions and the light areas are younger, tectonically deformed regions. The brownish-gray color is due to mixtures of rocky materials and ice. Bright spots are geologically recent impact craters and their ejecta. The finest details that can be discerned in this picture are about 13.4 km across. The images which combine for this color image were taken 26 June 1996 beginning at Universal Time 8:46:04

Credit: NASA/JPL