Panoramic view of an ice cliff inside the Sc?ri?oara Ice Cave, where the research was done.

Credit: Gigi Fratila & Claudiu Szabo

Ice cores drilled from a glacier in a cave in Transylvania offer new evidence of how Europe’s winter weather and climate patterns fluctuated during the last 10,000 years, known as the Holocene period.

The cores provide insights into how the region’s climate has changed over time. The researchers’ results, published this week in the journal Scientific Reports, could help reveal how the climate of the North Atlantic region, which includes the U.S., varies on long time scales.

The project, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Romanian Ministry of Education, involved scientists from the University of South Florida (USF), University of Belfast, University of Bremen and Stockholm University, among other institutions.

Researchers from the Emil Racoviță Institute of Speleology in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, and USF’s School of Geosciences gathered their evidence in the world’s most-explored ice cave and oldest cave glacier, hidden deep in the heart of Transylvania in central Romania.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

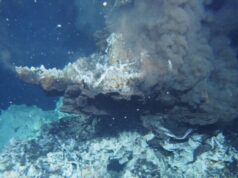

With its towering ice formations and large underground ice deposit, Scărișoara Ice Cave is among the most important scientific sites in Europe.

Scientist Bogdan Onac of USF and his colleague Aurel Perșoiu, working with a team of researchers in Scărișoara Ice Cave, sampled the ancient ice there to reconstruct winter climate conditions during the Holocene period.

Over the last 10,000 years, snow and rain dripped into the depths of Scărișoara, where they froze into thin layers of ice containing chemical evidence of past winter temperature changes.

Until now, scientists lacked long-term reconstructions of winter climate conditions. That knowledge gap hampered a full understanding of past climate dynamics, Onac said.

“Most of the paleoclimate records from this region are plant-based, and track only the warm part of the year — the growing season,” says Candace Major, program director in NSF’s Directorate for Geosciences, which funded the research. “That misses half the story. The spectacular ice cave at Scărișoara fills a crucial piece of the puzzle of past climate change in recording what happens during winter.”

Reconstructions of Earth’s climate record have relied largely on summer conditions, charting fluctuations through vegetation-based samples, such as tree ring width, pollen and organisms that thrive in the warmer growing season.

Absent, however, were important data from winters, Onac said.

Located in the Apuseni Mountains, the region surrounding the Scărișoara Ice Cave receives precipitation from the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea and is an ideal location to study shifts in the courses storms follow across East and Central Europe, the scientists say.

Radiocarbon dating of minute leaf and wood fragments preserved in the cave’s ice indicates that its glacier is at least 10,500 years old, making it the oldest cave glacier in the world and one of the oldest glaciers on Earth outside the polar regions.

From samples of the ice, the researchers were able to chart the details of winter conditions growing warmer and wetter over time in Eastern and Central Europe. Temperatures reached a maximum during the mid-Holocene some 7,000 to 5,000 years ago and decreased afterward toward the Little Ice Age, 150 years ago.

A major shift in atmospheric dynamics occurred during the mid-Holocene, when winter storm tracks switched and produced wetter and colder conditions in northwestern Europe, and the expansion of a Mediterranean-type climate toward southeastern Europe.

“Our reconstruction provides one of the very few winter climate reconstructions, filling in numerous gaps in our knowledge of past climate variability,” Onac said.

Warming winter temperatures led to rapid environmental changes that allowed the northward expansion of Neolithic farmers toward mainland Europe, and the rapid population of the continent.

“Our data allow us to reconstruct the interplay between Atlantic and Mediterranean sources of moisture,” Onac said. “We can also draw conclusions about past atmospheric circulation patterns, with implications for future climate changes. Our research offers a long-term context to better understand these changes.”

The results from the study tell scientists how the climate of the North Atlantic region, which includes the U.S., varies on long time scales. The scientists are continuing their cave study, working to extend the record back 13,000 years or more.

Sources: National Science Foundation

Research Reference:

Aurel Perșoiu, Bogdan P. Onac, Jonathan G. Wynn, Maarten Blaauw, Monica Ionita, Margareta Hansson. Holocene winter climate variability in Central and Eastern Europe.Scientific Reports, 2017; 7 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-01397-w