It’s impossible to obtain direct images of exoplanets as they are masked by the high luminous intensity of their stars. However, astronomers led by UNIGE propose detecting molecules present in the exoplanet’s atmosphere in order to make it visible, provided that these same molecules are absent from its star. The researchers have developed a device that is sensitive to the selected molecules, rendering the star invisible and allowing astronomers to observe the planet. The results appear in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Until now, only a few planets located very far from their host stars could be distinguished in an image, in particular thanks to the SPHERE instrument installed on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, and similar instruments elsewhere. Jens Hoeijmakers, researcher at the Astronomy Department of the Observatory of the Faculty of Science of the UNIGE and member of NCCR PlanetS, wondered if it would be possible to trace the molecular composition of the planets. “By focusing on molecules present only on the studied exoplanet that are absent from its host star, our technique would effectively “erase” the star, leaving only the exoplanet,” he explains.

To test this new technique, Hoeijmakers and an international team of astronomers used archival images taken by the SINFONI instrument of the star beta pictoris, which is known to be orbited by a giant planet, beta pictoris b. Each pixel in these images contains the spectrum of light received by that pixel. The astronomers then compared the spectrum contained in the pixel with a spectrum corresponding to a given molecule, for example water vapour, to see if there is a correlation. If there is a correlation, it means that the molecule is present in the atmosphere of the planet.

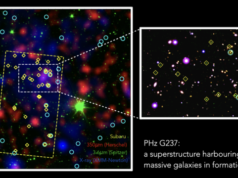

By applying this technique to beta pictoris b, the planet became perfectly visible when searching for water (H2O) or carbon monoxide (CO). However, when searching for methane (CH4) and ammonia (NH3), the planet remains invisible, suggesting the absence of these molecules in the atmosphere of beta pictoris b.

The host star beta pictoris remains invisible in all four situations. The star is extremely hot, and at this high temperature, these four molecules are destroyed. “This is why this technique allows us not only to detect elements on the surface of the planet, but also to sense the temperature that reigns there,” explains the astronomer. The fact that researchers cannot find beta pictoris b using the spectra of methane and ammonia is therefore consistent with a temperature estimated at 1700 degrees for the planet, which is too high for these molecules to exist.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

“This technique is only in its infancy,” says Hoeijmakers. “It should change the way planets and their atmospheres are characterized. We are very excited to see what it will give on future spectrographs like ERIS on the Very Large Telescope in Chile or HARMONI on the Extremely Large Telescope which will be inaugurated in 2025, also in Chile,” he says.

Provided by:

University of Geneva

More information:

H.J. Hoeijmakers et al. Medium-resolution integral-field spectroscopy for high-contrast exoplanet imaging: Molecule maps of the beta Pictoris system with SINFONI. Astronomy & Astrophysics (2018). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201832902

Image:

The planet becomes visible when looking for H2O or CO molecules. However, as there is no CH4 nor NH3 in its atmosphere, it remains invisble when looking for these molecules, just as its host star which contains none of those four elements

Credit: UNIGE