A team of astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has measured the universe’s expansion rate using a technique that is completely independent of any previous method.

Knowing the precise value for how fast the universe expands is important for determining the age, size, and fate of the cosmos. Unraveling this mystery has been one of the greatest challenges in astrophysics in recent years. The new study adds evidence to the idea that new theories may be needed to explain what scientists are finding.

The researchers’ result further strengthens a troubling discrepancy between the expansion rate, called the Hubble constant, calculated from measurements of the local universe and the rate as predicted from background radiation in the early universe, a time before galaxies and stars even existed.

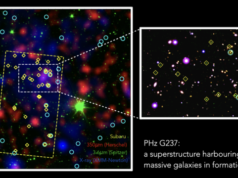

This latest value represents the most precise measurement yet using the gravitational lensing method, where the gravity of a foreground galaxy acts like a giant magnifying lens, amplifying and distorting light from background objects. This latest study did not rely on the traditional “cosmic distance ladder” technique to measure accurate distances to galaxies by using various types of stars as “milepost markers.” Instead, the researchers employed the exotic physics of gravitational lensing to calculate the universe’s expansion rate.

The astronomy team that made the new Hubble constant measurements is dubbed H0LiCOW (H0 Lenses in COSMOGRAIL’s Wellspring). COSMOGRAIL is the acronym for Cosmological Monitoring of Gravitational Lenses, a large international project whose goal is monitoring gravitational lenses. “Wellspring” refers to the abundant supply of quasar lensing systems.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

The research team derived the H0LiCOW value for the Hubble constant through observing and analysis techniques that have been greatly refined over the past two decades.

H0LiCOW and other recent measurements suggest a faster expansion rate in the local universe than was expected based on observations by the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite of how the cosmos behaved more than 13 billion years ago.

The gulf between the two values has important implications for understanding the universe’s underlying physical parameters and may require new physics to account for the mismatch.

“If these results do not agree, it may be a hint that we do not yet fully understand how matter and energy evolved over time, particularly at early times,” said H0LiCOW team leader Sherry Suyu of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany, the Technical University of Munich, and the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taipei, Taiwan.

How they did it

The H0LiCOW team used Hubble to observe the light from six faraway quasars, the brilliant searchlights from gas orbiting supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. Quasars are ideal background objects for many reasons; for example, they are bright, extremely distant, and scattered all over the sky. The telescope observed how the light from each quasar was multiplied into four images by the gravity of a massive foreground galaxy. The galaxies studied are 3 billion to 6.5 billion light-years away. The quasars’ average distance is 5.5 billion light-years from Earth.

The light rays from each lensed quasar image take a slightly different path through space to reach Earth. The pathway’s length depends on the amount of matter that is distorting space along the line of sight to the quasar. To trace each pathway, the astronomers monitor the flickering of the quasar’s light as its black hole gobbles up material. When the light flickers, each lensed image brightens at a different time.

This flickering sequence allows researchers to measure the time delays between each image as the lensed light travels along its path to Earth. To fully understand these delays, the team first used Hubble to make accurate maps of the distribution of matter in each lensing galaxy. Astronomers could then reliably deduce the distances from the galaxy to the quasar, and from Earth to the galaxy and to the background quasar. By comparing these distance values, the researchers measured the universe’s expansion rate.

“The length of each time delay indicates how fast the universe is expanding,” said team member Kenneth Wong of the University of Tokyo’s Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe, lead author of the H0LiCOW collaboration’s most recent paper. “If the time delays are shorter, then the universe is expanding at a faster rate. If they are longer, then the expansion rate is slower.”

The time-delay process is analogous to four trains leaving the same station at exactly the same time and traveling at the same speed to reach the same destination. However, each of the trains arrives at the destination at a different time. That’s because each train takes a different route, and the distance for each route is not the same. Some trains travel over hills. Others go through valleys, and still others chug around mountains. From the varied arrival times, one can infer that each train traveled a different distance to reach the same stop. Similarly, the quasar flickering pattern does not appear at the same time because some of the light is delayed by traveling around bends created by the gravity of dense matter in the intervening galaxy.

How it compares

The researchers calculated a Hubble constant value of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec (with 2.4% uncertainty). This means that for every additional 3.3 million light-years away a galaxy is from Earth, it appears to be moving 73 kilometers per second faster, because of the universe’s expansion.

The team’s measurement also is close to the Hubble constant value of 74 calculated by the Supernova H0 for the Equation of State (SH0ES) team, which used the cosmic distance ladder technique. The SH0ES measurement is based on gauging the distances to galaxies near and far from Earth by using Cepheid variable stars and supernovas as measuring sticks to the galaxies.

The SH0ES and H0LiCOW values significantly differ from the Planck number of 67, strengthening the tension between Hubble constant measurements of the modern universe and the predicted value based on observations of the early universe.

“One of the challenges we overcame was having dedicated monitoring programs through COSMOGRAIL to get the time delays for several of these quasar lensing systems,” said Frédéric Courbin of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, leader of the COSMOGRAIL project.

Suyu added: “At the same time, new mass modeling techniques were developed to measure a galaxy’s matter distribution, including models we designed to make use of the high-resolution Hubble imaging. The images enabled us to reconstruct, for example, the quasars’ host galaxies. These images, along with additional wider-field images taken from ground-based telescopes, also allow us to characterize the environment of the lens system, which affects the bending of light rays. The new mass modeling techniques, in combination with the time delays, help us to measure precise distances to the galaxies.”

Begun in 2012, the H0LiCOW team now has Hubble images and time-delay information for 10 lensed quasars and intervening lensing galaxies. The team will continue to search for and follow up on new lensed quasars in collaboration with researchers from two new programs. One program, called STRIDES (STRong-lensing Insights into Dark Energy Survey), is searching for new lensed quasar systems. The second, called SHARP (Strong-lensing at High Angular Resolution Program), uses adaptive optics with the W.M. Keck telescopes to image the lensed systems. The team’s goal is to observe 30 more lensed quasar systems to reduce their 2.4% percent uncertainty to 1%.

NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, expected to launch in 2021, may help them achieve their goal of 1% uncertainty much faster through Webb’s ability to map the velocities of stars in a lensing galaxy, which will allow astronomers to develop more precise models of the galaxy’s distribution of dark matter.

The H0LiCOW team’s work also paves the way for studying hundreds of lensed quasars that astronomers are discovering through surveys such as the Dark Energy Survey and PanSTARRS (Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System), and the upcoming National Science Foundation’s Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which is expected to uncover thousands of additional sources.

In addition, NASA’s Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) will help astronomers address the disagreement in the Hubble constant value by tracing the expansion history of the universe. The mission will also use multiple techniques, such as sampling thousands of supernovae and other objects at various distances, to help determine whether the discrepancy is a result of measurement errors, observational technique, or whether astronomers need to adjust the theory from which they derive their predictions.

The team will present its results at the 235th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Provided by: ESA/Hubble Information Centre

More information: Kenneth C. Wong, et al. H0LiCOW XIII. A 2.4% measurement of H0 from lensed quasars: 5.3σ tension between early and late-Universe probes. arXiv:1907.04869v2

Image: Each of these Hubble Space Telescope snapshots reveals four distorted images of a background quasar surrounding the central core of a foreground massive galaxy. The multiple quasar images were produced by the gravity of the foreground galaxy, which is acting like a magnifying glass by warping the quasar’s light in an effect called gravitational lensing. Quasars are extremely distant cosmic streetlights produced by active black holes. The light rays from each lensed quasar image take a slightly different path through space to reach Earth. The pathway’s length depends on the amount of matter that is distorting space along the line of sight to the quasar. To trace each pathway, the astronomers monitor the flickering of the quasar’s light as its black hole gobbles up material. When the light flickers, each lensed image brightens at a different time. This flickering sequence allows researchers to measure the time delays between each image as the lensed light travels along its path to Earth. These time-delay measurements helped astronomers calculate how fast the universe is growing, a value called the Hubble constant.

Credit: NASA, ESA, S.H. Suyu (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Technical University of Munich, and Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics), and K.C. Wong (University of Tokyo’s Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe)