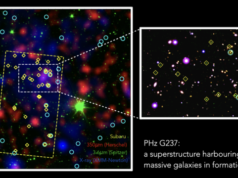

International astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have made an independent measurement of how fast the Universe is expanding. The newly measured expansion rate for the local Universe is consistent with earlier findings. These are, however, in intriguing disagreement with measurements of the early Universe. Credit: NASA, ESA, Suyu (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics), Auger (University of Cambridge)

The Hubble constant—the rate at which the Universe is expanding—is one of the fundamental quantities describing our Universe. A group of astronomers from the H0LiCOW collaboration, led by Sherry Suyu, Max Planck professor at the Technical University Munich (TUM) and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching, Germany, used the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and other telescopes in space and on the ground to observe five galaxies in order to arrive at an independent measurement of the Hubble constant..

This research was presented in a series of papers to appear in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The new measurement is completely independent of—but in excellent agreement with—other measurements of the Hubble constant in the local Universe that used Cepheid variable stars and supernovae as points of reference [heic1611].

However, the value measured by Suyu and her team, as well as those measured using Cepheids and supernovae, are different from the measurement made by the ESA Planck satellite. But there is an important distinction—Planck measured the Hubble constant for the early Universe by observing the cosmic microwave background.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

While the value for the Hubble constant determined by Planck fits with our current understanding of the cosmos, the values obtained by the different groups of astronomers for the local Universe are in disagreement with our accepted theoretical model of the Universe. “The expansion rate of the Universe is now starting to be measured in different ways with such high precision that actual discrepancies may possibly point towards new physics beyond our current knowledge of the Universe,” elaborates Suyu.

The targets of the study were massive galaxies positioned between Earth and very distant quasars—incredibly luminous galaxy cores. The light from the more distant quasars is bent around the huge masses of the galaxies as a result of strong gravitational lensing. This creates multiple images of the background quasar, some smeared into extended arcs.

Because galaxies do not create perfectly spherical distortions in the fabric of space and the lensing galaxies and quasars are not perfectly aligned, the light from the different images of the background quasar follows paths which have slightly different lengths. Since the brightness of quasars changes over time, astronomers can see the different images flicker at different times, the delays between them depending on the lengths of the paths the light has taken. These delays are directly related to the value of the Hubble constant. “Our method is the most simple and direct way to measure the Hubble constant as it only uses geometry and General Relativity, no other assumptions,” explains co-lead Frédéric Courbin from the Laboratory of Astrophysics, Lastro (EPFL), Switzerland.

Using the accurate measurements of the time delays between the multiple images, as well as computer models, has allowed the team to determine the Hubble constant to an impressively high precision: 3.8 percent. “An accurate measurement of the Hubble constant is one of the most sought-after prizes in cosmological research today,” highlights team member Vivien Bonvin, from EPFL, Switzerland. And Suyu adds: “The Hubble constant is crucial for modern astronomy as it can help to confirm or refute whether our picture of the Universe—composed of dark energy, dark matter and normal matter—is actually correct, or if we are missing something fundamental.”

Source: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center