Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have completed an unprecedented “dissection” of twin galaxies in the final stages of merging.

The new study, led by CU Boulder research associate Francisco Müller-Sánchez, explores a galaxy called NGC 6240. While most galaxies in the universe hold only one supermassive black hole at their center, NGC 6240 contains two — and they’re circling each other in the last steps before crashing together.

The research reveals how gases ejected by those spiraling black holes, in combination with gases ejected by stars in the galaxy, may have begun to power down NGC 6240’s production of new stars. Müller-Sánchez’s team also shows how these “winds” have helped to create the galaxy’s most tell-tale feature: a massive cloud of gas in the shape of a butterfly.

“We dissected the butterfly,” said Müller-Sánchez of CU Boulder’s Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS). “This is the first galaxy in which we can see both the wind from the two supermassive black holes and the outflow of low ionization gas from star formation at the same time.”

The team zeroed in on NGC 6240, in part, because galaxies with two supermassive black holes at their centers are relatively rare. Some experts also suspect that those twin hearts have given rise to the galaxy’s unusual appearance. Unlike the Milky Way, which forms a relatively tidy disk, bubbles and jets of gas shoot off from NGC 6240, extending more than 30,000 light years into space and resembling a butterfly in flight.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

“Galaxies with a single supermassive black hole never show such a phenomenal structure,” Müller-Sánchez said.

In research that will be published April 18 in Nature, the team discovered that two different forces have given rise to the nebula. The butterfly’s northwest corner, for example, is the product of stellar winds, or gases that stars emit through various processes. The northeast corner, on the other hand, is dominated by a single cone of gas that was ejected by the pair of black holes — the result of those black holes gobbling up large amounts of galactic dust and gas during their merger.

Those two winds combined evict about 100 times the mass of Earth’s sun in gases from the galaxy every year. That’s a “very large number, comparable to the rate at which the galaxy is creating stars in the nuclear region,” Müller-Sánchez said.

Such an outflow can have big implications for the galaxy itself. He explained that when two galaxies merge, they begin a feverish burst of new star formation. Black hole and stellar winds, however, can slow down that process by clearing away the gases that make up fresh stars — much like how a gust of wind can blow away the pile of leaves you just raked.

“NGC 6240 is in a unique phase of its evolution,” said Julie Comerford, an assistant professor in APS at CU Boulder and a co-author of the new study. “It is forming stars intensely now, so it needs the extra strong kick of two winds to slow down that star formation and evolve into a less active galaxy.”

Provided by:

University of Colorado at Boulder

More information:

F. Müller-Sánchez, R. Nevin, J. M. Comerford, R. I. Davies, G. C. Privon, E. Treister. Two separate outflows in the dual supermassive black hole system NGC 6240. Nature, 2018; 556 (7701): 345 DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0033-2

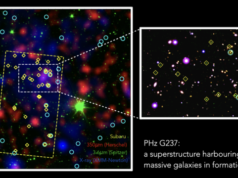

Image:

NGC 6240 as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope

Credit: NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration, and A. Evans (University of Virginia, Charlottesville/NRAO/Stony Brook University