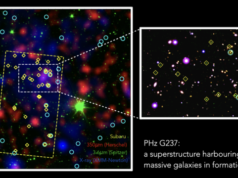

This X-ray image shows extended emission around a source known as Swift J1834.9-0846, a rare ultra-magnetic neutron star called a magnetar. The glow arises from a cloud of fast-moving particles produced by the neutron star and corralled around it. Color indicates X-ray energies, with 2,000-3,000 electron volts (eV) in red, 3,000-4,500 eV in green, and 5,000 to 10,000 eV in blue. The image combines observations by the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton spacecraft taken on March 16 and Oct. 16, 2014. Credit: ESA/XMM-Newton/Younes et al. 2016

Astronomers have discovered a vast cloud of high-energy particles called a wind nebula around a rare ultra-magnetic neutron star, or magnetar, for the first time. The find offers a unique window into the properties, environment and outburst history of magnetars, which are the strongest magnets in the universe.

A neutron star is the crushed core of a massive star that ran out of fuel, collapsed under its own weight, and exploded as a supernova. Each one compresses the equivalent mass of half a million Earths into a ball just 12 miles (20 kilometers) across, or about the length of New York’s Manhattan Island. Neutron stars are most commonly found as pulsars, which produce radio, visible light, X-rays and gamma rays at various locations in their surrounding magnetic fields. When a pulsar spins these regions in our direction, astronomers detect pulses of emission, hence the name.

Typical pulsar magnetic fields can be 100 billion to 10 trillion times stronger than Earth’s. Magnetar fields reach strengths a thousand times stronger still, and scientists don’t know the details of how they are created. Of about 2,600 neutron stars known, to date only 29 are classified as magnetars.

The newfound nebula surrounds a magnetar known as Swift J1834.9-0846 — J1834.9 for short — which was discovered by NASA’s Swift satellite on Aug. 7, 2011, during a brief X-ray outburst. Astronomers suspect the object is associated with the W41 supernova remnant, located about 13,000 light-years away in the constellation Scutum toward the central part of our galaxy.

“Right now, we don’t know how J1834.9 developed and continues to maintain a wind nebula, which until now was a structure only seen around young pulsars,” said lead researcher George Younes, a postdoctoral researcher at George Washington University in Washington. “If the process here is similar, then about 10 percent of the magnetar’s rotational energy loss is powering the nebula’s glow, which would be the highest efficiency ever measured in such a system.”

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

A month after the Swift discovery, a team led by Younes took another look at J1834.9 using the European Space Agency’s (ESA) XMM-Newton X-ray observatory, which revealed an unusual lopsided glow about 15 light-years across centered on the magnetar. New XMM-Newton observations in March and October 2014, coupled with archival data from XMM-Newton and Swift, confirm this extended glow as the first wind nebula ever identified around a magnetar. A paper describing the analysis will be published by The Astrophysical Journal.

“For me the most interesting question is, why is this the only magnetar with a nebula? Once we know the answer, we might be able to understand what makes a magnetar and what makes an ordinary pulsar,” said co-author Chryssa Kouveliotou, a professor in the Department of Physics at George Washington University’s Columbian College of Arts and Sciences.

The most famous wind nebula, powered by a pulsar less than a thousand years old, lies at the heart of the Crab Nebula supernova remnant in the constellation Taurus. Young pulsars like this one rotate rapidly, often dozens of times a second. The pulsar’s fast rotation and strong magnetic field work together to accelerate electrons and other particles to very high energies. This creates an outflow astronomers call a pulsar wind that serves as the source of particles making up in a wind nebula.

“Making a wind nebula requires large particle fluxes, as well as some way to bottle up the outflow so it doesn’t just stream into space,” said co-author Alice Harding, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We think the expanding shell of the supernova remnant serves as the bottle, confining the outflow for a few thousand years. When the shell has expanded enough, it becomes too weak to hold back the particles, which then leak out and the nebula fades away.” This naturally explains why wind nebulae are not found among older pulsars, even those driving strong outflows.

A pulsar taps into its rotational energy to produce light and accelerate its pulsar wind. By contrast, a magnetar outburst is powered by energy stored in the super-strong magnetic field. When the field suddenly reconfigures to a lower-energy state, this energy is suddenly released in an outburst of X-rays and gamma rays. So while magnetars may not produce the steady breeze of a typical pulsar wind, during outbursts they are capable of generating brief gales of accelerated particles.

“The nebula around J1834.9 stores the magnetar’s energetic outflows over its whole active history, starting many thousands of years ago,” said team member Jonathan Granot, an associate professor in the Department of Natural Sciences at the Open University in Ra’anana, Israel. “It represents a unique opportunity to study the magnetar’s historical activity, opening a whole new playground for theorists like me.”

ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite was launched on Dec. 10, 1999, from Kourou, French Guiana, and continues to make observations. NASA funded elements of the XMM-Newton instrument package and provides the NASA Guest Observer Facility at Goddard, which supports use of the observatory by U.S. astronomers.

Source: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Journal: Astrophysical Journal