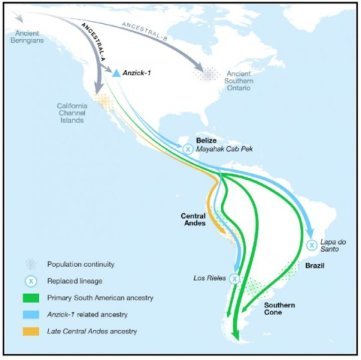

An international research team has used genome-wide ancient DNA data to revise Central and South American history. Their analysis of DNA from 49 individuals spanning about 10,000 years in Belize, Brazil, the Central Andes, and southern South America has concluded that the majority of Central and South American ancestry arrived from at least three different streams of people entering from North America, all arising from one ancestral lineage of migrants who crossed the Bering Strait some time before 15,000 years ago.

The evidence, presented November 8 in the journal Cell, shows that within this one ancestral lineage, there were two previously undocumented streams of gene flow from North to South America, one of which was later displaced in a major population replacement that began at least 9,000 years ago.

“Our work multiplied the number of ancient genomes available from these areas by about 20, giving us a much more comprehensive picture of indigenous history in the Americas,” says co-senior author David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “This broader dataset reveals a common origin of North, Central, and South Americans as well as two previously unknown genetic exchanges between North and South America.”

“Nearly all Central and South Americans arose from a star-like radiation of the first lineage into at least three branches,” says co-lead author Cosimo Posth, an archaeogeneticist from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “That means that nearly all the ancestry of Central and South Americans came from the same source population, albeit one that had already diversified prior to its spread into South America. With DNA evidence largely based on present-day people, those multiple gene flow events are undetectable, highlighting the power of ancient DNA data.”

The genome analysis also yielded new insights on the Clovis culture-related people, who were mainly distributed across North America from about 13,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence from Clovis sites shows that the spread of Clovis artefacts did not expand throughout South America. But when the researchers used genome-sequencing technology to generate and compare genomes from a previously published ~13,000-year-old Clovis-related genome in Montana to the earliest genomes analyzed from South and Central America dating to between ~9,000 and ~11,000 years ago, they noticed significant shared ancestry. That suggested that the people who spread the Clovis culture also left a major impact much father south through people producing non-Clovis-specific stone tools.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

“We weren’t expecting to find a relation to people associated with the Clovis culture in South America,” says co-first author Nathan Nakatsuka, a PhD student in Reich’s lab at Harvard. “But it seems the expansion of the Clovis-associated lineage extended to parts of Central and South America.”

The paper concludes that this Clovis-related lineage contributed substantially to a group of 9,000-10,000-year-old individuals from Lagoa Santa in Brazil, inconsistent with the hypothesis that the people from this site derived from a separate migration from Asia. The authors also detected the Clovis-related genetic affinity in an even older, almost ~11,000-year-old individual from Chile and a slightly younger, more than ~9,000-year-old individual from Belize.

Beginning around ~9,000 years ago with ancient samples in Peru, however, the authors detected an almost complete disappearance of the Clovis culture-associated ancestry in Central and South America, documenting a remarkable population replacement. The large-scale population replacement is a process that was not widely expected by archaeologists,” says Reich. “This is an exciting example of how ancient DNA studies can reveal events in the past that were not confirmed and thus can stimulate new work in archaeology.”

The researchers also showed that after this major population turnover, there was striking continuity compared to other parts of the world like Eurasia and Africa. “There is remarkable continuity between earlier and later skeletons with South Americans today,” says Posth. “For example, modern-day Quechua and Aymara from the Central Andes can trace their ancestry back to the ancient people of the Cuncaicha site from 9,000 years ago onwards. This is a longer-standing continuity than you see in other continents.”

The researchers recognize that there is much more work to do to fully flesh out the history of the Americas.

“We’re very enthusiastic about the prospects for a much richer understanding of American population history, but this is still a vast region full of geographic and chronological holes,” says Reich. “We’d like to collect more genetic material from earlier and later sites and from more countries, such as Colombia, Venezuela, and other parts of Brazil. We also want to examine the evolution of genetic traits over time.”

Provided by:

Cell Press

More information:

Posth et al. Reconstructing the Deep Population History of Central and South America. Cell (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.027

Image:

This map depicts the findings of Posth et al., who conducted a large-scale analysis of ancient genomes from Central and South America yields insights into the peopling of the Americas, including four southward migration events and notable population continuity in much of South America after arrival.

Credit: Posth et al./Cell