RainCube, due to fly in 2017, forced JPL’s engineers to get creative in order to squeeze an antenna into a CubeSat. Credit: Tyvak/Jonathan Sauder/NASA/JPL-Caltech

Black magic.

That’s what radiofrequency engineers call the mysterious forces guiding communications over the air. These forces involve complex physics and are difficult enough to master on Earth. They only get more baffling when you’re beaming signals into space.

Until now, the shape of choice for casting this “magic” has been the parabolic dish. The bigger the antenna dish, the better it is at “catching” or transmitting signals from far away.

But CubeSats are changing that. These spacecraft are meant to be light, cheap and extremely small: most aren’t much bigger than a cereal box. Suddenly, antenna designers have to pack their “black magic” into a device where there’s no room for a dish — let alone much else.

“It’s like pulling a rabbit out of a hat,” said Nacer Chahat, a specialist in antenna design at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “Shrinking the size of the radar is a challenge for NASA. As space engineers, we usually have lots of volume, so building antennas packed into a small volume isn’t something we’re trained to do.”

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

Challenge accepted.

Chahat and his team have been pushing the limits of antenna designs, and recently worked with a CubeSat team on the antenna for Radar In a CubeSat (RainCube), a technology demonstration mission scheduled for launch in 2018. RainCube’s distinctive antenna looks a little like an umbrella stuffed into a jack-in-the-box; when open, its ribs extend out of a canister and splay out a golden mesh.

As its name suggests, RainCube will use radar to measure rain and snowfall. CubeSats are measured in increments of 1U (A CubeSat unit, or 1U, is roughly equivalent to a 4-inch cubic box, or 10x10x10 cubic centimeters). The RainCube antenna has to be small enough to be crammed into a 1.5U container. Think of it as an antenna in a can, with no spare room for anything else.

“Large, deployable antennas that can be stowed in a small volume are a key technology for radar missions,” said JPL’s Eva Peral, principal investigator for RainCube. “They open a new realm of possibilities for science advancement and unique applications.”

To maintain its relatively small size, the antenna relies on the high-frequency, Ka-band wavelength — something that’s still rare for NASA CubeSats, but is ideally suited to RainCube. But Ka-band has other uses besides radar. It allows for an exponential increase in data transfer over long distances, making it the perfect tool for telecommunications.

Ka-band allows for data rates about 16 times higher than X-band, the current standard on most NASA spacecraft.

In that sense, the development of RainCube’s antenna can test the use of CubeSats more generally. While most have been limited to simple studies in near-Earth orbit, the right technology could allow them to be used as far away as Mars or beyond. That might open up CubeSats to a whole range of future missions.

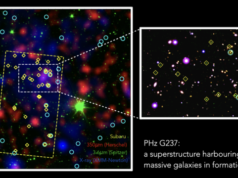

The team that developed the Mars Cube One (MarCo) high-gain antenna. Group Supervisor Richard Hodges (far left) and Nacer Chahat (in back with black shirt) designed the high-gain antenna. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“To enable the next step in CubeSat evolution, you need this kind of technology,” said JPL’s Jonathan Sauder, mechanical engineer lead for the RainCube antenna.

Chahat was brought on to the RainCube team after he worked on another innovative antenna design. The MarCO (Mars Cube One) mission consists of a pair of Cubesats that have been proposed to fly in 2018 with NASA’s InSight lander, which would measure the Red Planet’s tectonics for the first time. While InSight is touching down, the two MarCO CubeSats would relay information about the landing back to Earth. Just like RainCube, MarCO is primarily a technology demonstration; it would test how future missions could use CubeSats to carry communication relays with them, enabling researchers to know what’s happening on the ground much faster.

The MarCO design looks nothing like a typical antenna. In place of a round dish are three flat panels dotted with reflective material. The shape and size of these dots form concentric rings that mimic the curve of a dish. Just as a dish might, this mosaic pattern of dots focuses the signal radiated from the antenna’s feed towards Earth.

“New technologies like these allow NASA and JPL to do more with less,” said JPL’s John Baker, program manager for MarCO. “We want to make it possible to explore anywhere we want in the solar system.”

Both RainCube and MarCO highlight creative workarounds to the size limits of CubeSats. The next trick for Chahat and his colleagues will be combining those designs into an even bigger antenna: a reflectarray ranging 3.3 feet by 3.3 feet (1 meter by 1 meter) and made up of 15 flat panels. These segmented panels would unfold like the flat surface of MarCo’s, while the antenna’s feed would telescope out like RainCube’s antenna. This antenna would be called OMERA, short for the One Meter Reflectarray.

“If we can extend the technology to one meter in size, the OMERA antenna will push the limits of what can be practically flown today on a CubeSat,” said Tom Cwik, manager of space technology at JPL.

A prototype of the OMERA CubeSat is expected to be ready by March of 2017.

“OMERA’s larger array will produce higher gain for telecommunications applications, or will produce narrower beam widths for Earth science needs,” Chahat said. That means we would be able to venture even farther into deep space and will have even more powerful and accurate radars.”

Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory