The shower of electrons bouncing across Earth’s magnetosphere — commonly known as the Northern Lights — has been directly observed for the first time by an international team of scientists. While the cause of these colorful auroras has long been hypothesized, researchers had never directly observed the underlying mechanism until now.

The scientists published their results today in Nature.

The spectacle of these subatomic showers is legendary. Green, red, and purple waltz across the night sky, blending into one another for a fantastic show widely considered one of the great wonders of the world. Among a variety of auroras, pulsating auroral patches appearing at dawn are common but the physical mechanisms driving this auroral pulsation had so far not been verified through observation.

With the advent of a new satellite with advanced measuring tools, researchers have now identified that this wonder is caused by the hard-to-detect interaction between electrons and plasma waves. This interaction takes place in the Earth’s magnetosphere, the region surrounding the Earth in which the behavior of the electric particles is usually governed by the planet’s magnetic field.

“Auroral substorms … are caused by global reconfiguration in the magnetosphere, which releases stored solar wind energy,” writes Satoshi Kasahara, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the Graduate School of Science of the University of Tokyo in Japan, the lead author of the paper. “They are characterized by auroral brightening from dusk to midnight, followed by violent motions of distinct auroral arcs that eventually break up, and emerge as diffuse, pulsating auroral patches at dawn.”

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

The global reconfiguration often drives a specific type of plasma waves called chorus waves, to rain electrons into the upper atmosphere. This stabilizes the system, and gives off a colorful light as the electrons fall. However, scientists have questioned if the chorus waves were powerful enough to excite electrons to the extent of creating auroras.

“We, for the first time, directly observed scattering of electrons by chorus waves generating particle precipitation into the Earth’s atmosphere,” Kasahara says. “The precipitating electron flux was sufficiently intense to generate pulsating aurora.”

Scientists couldn’t see this direct evidence of electron scattering before because typical electron sensors cannot distinguish the precipitating electrons from others. Kasahara and his team designed a specialized electron sensor that observed the precise interactions of auroral electrons driven by chorus waves. The sensor was aboard the Exploration of energization and Radiation in Geospace (ERG) satellite, also known as the Arase spacecraft, launched by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

The scientists plan to pursue this line of research further. The collaborative team includes not only researchers from the University of Tokyo, but also Nagoya University, Osaka University, the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Kanazawa University, and Tohoku University in Japan; the Academic Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan; and the University of California, Berkeley and the University of California, Los Angeles in the U.S.

“By analyzing data collected by the ERG spacecraft more comprehensively, we will reveal the variability and further details of plasma physics and resulting atmospheric phenomena, such as auroras,” Kasahara says.

Provided by:

University of Tokyo

More information:

S. Kasahara, Y. Miyoshi, S. Yokota, T. Mitani, Y. Kasahara, S. Matsuda, A. Kumamoto, A. Matsuoka, Y. Kazama, H. U. Frey, V. Angelopoulos, S. Kurita, K. Keika, K. Seki, I. Shinohara. Pulsating aurora from electron scattering by chorus waves. Nature, 2018; 554 (7692): 337 DOI: 10.1038/nature25505

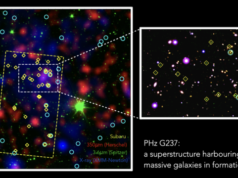

Image:

The ERG spacecraft observed chorus waves and scattered electrons in the magnetosphere, the origin of pulsation auroras. The scattered electrons precipitated into the atmosphere resulting in auroral illumination. Intermittent occurrence of chorus waves and associated electron scattering lead to auroral pulsation.

Credit: 2018 ERG science team