Researchers from the University of Houston and the California Institute of Technology have reported an inexpensive hybrid catalyst capable of splitting water to produce hydrogen, suitable for large-scale commercialization.

Most systems to split water into its components — hydrogen and oxygen — require two catalysts, one to spur a reaction to separate the hydrogen and a second to produce oxygen. The new catalyst, made of iron and dinickel phosphides on commercially available nickel foam, performs both functions.

Researchers said it has the potential to dramatically lower the amount of energy required to produce hydrogen from water while generating a high current density, a measure of hydrogen production. Lower energy requirements means the hydrogen could be produced at a lower cost.

“It puts us closer to commercialization,” said Zhifeng Ren, M.D. Anderson Chair Professor of physics at UH and lead author of a paper describing the new catalyst published Friday in Nature Communications.

Hydrogen is considered a desirable source of clean energy, in the form of fuel cells to power electric motors or burned in internal combustion engines, along with a number of industrial uses. Because it can be compressed or converted to liquid, it is more easily stored than some other forms of energy, said Ren, who also is a researcher at the Texas Center for Superconductivity at UH.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

But finding a practical, inexpensive and environmentally friendly way to produce large amounts of hydrogen gas — especially by splitting water into its component parts — has been a challenge.

Most hydrogen is currently produced through steam methane reforming and coal gasification; those methods raise the fuel’s carbon footprint despite the fact that it burns cleanly.

And while traditional catalysts can produce hydrogen from water, co-author Shuo Chen, assistant professor of physics at UH, said they generally rely on expensive platinum group elements. That raises the cost, making large-scale water splitting impractical.

“In contrast, our materials are based on earth abundant elements and exhibit comparable performance with those of platinum group materials,” she said. “It can be potentially scaled-up at low cost, which makes it very attractive and promising for the commercialization of water splitting.”

Researchers said the catalyst remained stable and effective through more than 40 hours of testing.

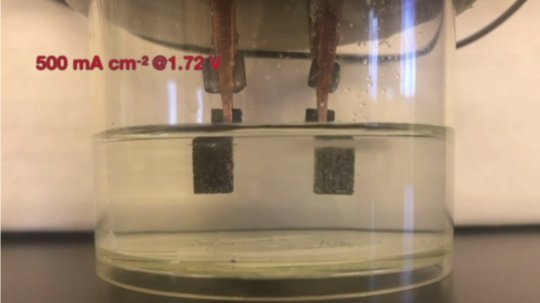

The new catalyst, they wrote, “proves to be an outstanding bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting, exhibiting both extremely high OER (oxygen evolution reaction) and HER (hydrogen evolution reaction) activities in the same alkaline electrolyte. Indeed, it sets a new record in alkaline water electrolyzers (1.42 V to afford 10 mA cm-2), while at the commercially practical current density of 500 mA cm-2.”

Previous catalysts have used different materials to spur a reaction to produce the hydrogen than those that are used to produce the oxygen. Ren said the interaction between the iron phosphide particles and the dinickel phosphide particles boosted both reactions. “Somehow a joint effort of the two materials is better than any individual material,” he said.

In addition to Ren and Chen, other authors on the paper include Fang Yu, Haiqing Zhou and Jingying Sun, all with the UH Department of Physics; Fan Qin and Jiming Bao, with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at UH; and Yufeng Huang and William A. Goddard III of the Materials and Process Simulation Center at the California Institute of Technology.

Provided by:

University of Houston

More information:

Fang Yu, Haiqing Zhou, Yufeng Huang, Jingying Sun, Fan Qin, Jiming Bao, William A. Goddard, Shuo Chen, Zhifeng Ren. High-performance bifunctional porous non-noble metal phosphide catalyst for overall water splitting. Nature Communications, 2018; 9 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04746-z

Image:

Screenshot of video showing hybrid catalyst for water splitting (see video at: https://youtu.be/nkouqCFaqAk).

Credit: Image courtesy of University of Houston