A Princeton team has developed a class of light-switchable, highly adaptable molecular tools with new capabilities to control cellular activities. The antibody-like proteins, called OptoBinders, allow researchers to rapidly control processes inside and outside of cells by directing their localization, with potential applications including protein purification, the improved production of biofuels, and new types of targeted cancer therapies

In a pair of papers published Aug. 13 in Nature Communications, the researchers describe the creation of OptoBinders that can specifically latch onto a variety of proteins both inside and outside of cells. OptoBinders can bind or release their targets in response to blue light. The team reported that one type of OptoBinder changed its affinity for its target molecules up to 330-fold when shifted from dark to blue light conditions, while others showed a five-fold difference in binding affinity—all of which could be useful to researchers seeking to understand and engineer the behaviors of cells.

Crucially, OptoBinders can target proteins that are naturally present in cells, and their binding is easily reversible by changing light conditions—”a new capability that is not available to normal antibodies,” said co-author José Avalos, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment. “The ability to let go [of a target protein] is actually very valuable for many applications,” said Avalos, including engineering cells’ metabolisms, purifying proteins or potentially making biotherapeutics.

The new technique is the latest in a collaboration between Avalos and Jared Toettcher, an assistant professor of molecular biology. Both joined the Princeton faculty in 2015, and soon began working together on new ways to apply optogenetics—a set of techniques that introduce genes encoding light-responsive proteins to control cells’ behaviors.

“We hope that this is going to be the beginning of the next era of optogenetics, opening the door to light-sensitive proteins that can interface with virtually any protein in biology, either inside or outside of cells,” said Toettcher, the James A. Elkins, Jr. ’41 Preceptor in Molecular Biology.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

Avalos and his team hope to use OptoBinders to control the metabolisms of yeast and bacteria to improve the production of biofuels and other renewable chemicals, while Toettcher’s lab is interested in the molecules’ potential to control signaling pathways involved in cancer.

The two papers describe different types of light-switchable binders: opto-nanobodies and opto-monobodies. Nanobodies are derived from the antibodies of camelids, the family of animals that includes camels, llamas and alpacas, which produce some antibodies that are smaller (hence the name nanobody) and simpler in structure than those of humans or other animals.

Nanobodies’ small size makes them more adaptable and easier to work with than traditional antibodies; they recently received attention for their potential as a COVID-19 therapy. Monobodies, on the other hand, are engineered pieces of human fibronectin, a large protein that forms part of the matrix between cells.

“These papers go hand in hand,” said Avalos. “The opto-nanobodies take advantage of the immune systems of these animals, and the monobodies have the advantage of being synthetic, which gives us opportunities to further engineer them in different ways.”

The two types of OptoBinders both incorporate a light-sensitive domain from a protein found in oat plants.

“When you turn the light on and off, these tools bind and release their target almost immediately, so that brings another level of control” that was not previously possible, said co-author César Carrasco-López, an associate research scholar in Avalos’ lab. “Whenever you are analyzing things as complex as metabolism, you need tools that allow you to control these processes in a complex way in order to understand what is happening.”

In principle, OptoBinders could be engineered to target any protein found in a cell. With most existing optogenetic systems, “you always had to genetically manipulate your target protein in a cell for each particular application,” said co-author Agnieszka Gil, a postdoctoral research fellow in Toettcher’s lab. “We wanted to develop an optogenetic binder that did not depend on additional genetic manipulation of the target protein.”

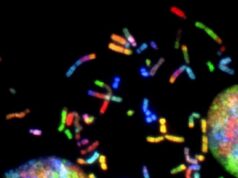

In a proof of principle, the researchers created an opto-nanobody that binds to actin, a major component of the cytoskeleton that allows cells to move, divide and respond to their environment. The opto-nanobody strongly bound to actin in the dark, but released its hold within two minutes in the presence of blue light. Actin proteins normally join together to form filaments just inside the cell membrane and networks of stress fibers that traverse the cell. In the dark, the opto-nanobody against actin binds to these fibers; in the light, these binding interactions are disrupted, causing the opto-nanobody to scatter throughout the cell. The researchers could even manipulate binding interactions on just one side of a cell—a level of localized control that opens new possibilities for cell biology research.

OptoBinders stand to unlock scores of innovative, previously inaccessible uses in cell biology and biotechnology, said Andreas Möglich, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Bayreuth in Germany who was not involved in the studies. But, Möglich said, “there is much more to the research” because the design strategy can be readily translated to other molecules, paving the way to an even wider repertoire of customized, light-sensitive binders.

“The impressive results mark a significant advance,” he said.

“Future applications will depend on being able to generate more OptoBinders” against a variety of target proteins, said Carrasco-López. “We are going to try to generate a platform so we can select OptoBinders against different targets” using a standardized, high-throughput protocol, he said, adding that this is among the first priorities for the team as they resume their experiments after lab research was halted this spring due to COVID-19.

Beyond applications that involve manipulating cell metabolism for microbial chemical production, Avalos said, OptoBinders could someday be used to design biomaterials whose properties can be changed by light.

The technology also holds promise as way to reduce side effects of drugs by focusing their action to a specific site in the body or adjusting dosages in real time, said Toettcher, who noted that applying light inside the body would require a device such as an implant. “There aren’t many ways to do spatial targeting with normal pharmacology or other techniques, so having that kind of capability for antibodies and therapeutic binders would be a really cool thing,” he said. “We think of this as a sea change in what sorts of processes can be placed under optogenetic control.”

Provided by: Princeton University

More information: César Carrasco-López et al. Development of light-responsive protein binding in the monobody non-immunoglobulin scaffold. Nature Communications (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-17837-7

Image: This time-lapse movie shows a new tool called an OptoBinder that can latch onto and release molecules in response to light. In this case, a fluorescent OptoBinder is attaching to actin, a component of cells key to their structure and shape. The OptoBinder strongly binds to actin in the dark, but releases its hold in the presence of blue light (indicated by blue box at top right).

Credit: Video courtesy of the researchers; GIF by Bumper DeJesus