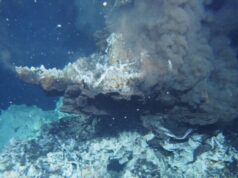

By recording activity in the brain of a restrained cockroach, researchers found the insects use sight and a vestibular-like system to track direction and angle.

Credit: Varga et al/Current Biology

Rats, men and cockroaches appear to have a similar GPS in their heads that allows them to navigate new surroundings, researchers at Case Western Reserve University report.

The finding, published in journal Current Biology, is likely an example of convergent evolution–that is, distinct animals developed similar systems to manage the same problems.

Due to their simpler brain, further studies on cockroaches that would be difficult–if not impossible–on mammals may yield new insights into how humans orient themselves and navigate. Or, what goes awry in people who have extreme trouble getting their bearings.

“We’ve known that a mammal can come into a new area and, after a short period of being disoriented, find its way around,” said Roy Ritzmann, a biology professor at Case Western Reserve and an author of the new study.

Humans and other mammals rely on head-direction, place and grid cells in their brains to process, integrate and update sensory information. The cues come from the direction they look, what they see and motion, he said.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

Insects must maneuver through new environments, too.

“Orienting contributes to spatial memory, so they can return to point A or navigate to something they like or away from something they don’t like,” said PhD student Adrienn G. Varga, lead author of the study.

By repeating experiments that uncovered head-direction cells in rats, Ritzmann and Varga found head-direction-like activity and evidence of contextual cue processing in cockroaches.

The experiment

The researchers recorded cell activities in an area of the brain called the central complex while roaches were restrained in a tube.

Each roach was placed on a platform that rotated clockwise or counter clockwise. The platform was encircled by a black wall with a single removable landmark: a white square.

The insects were rotated 360 degrees in 30-degree increments, four to six times, both clockwise and counterclockwise.

Roaches could see, and though they lack an inner ear, have a vestibular-like system that appears to provide directional cues.

Similar to humans, who appear to have different cells that fire when turning clockwise compared to counterclockwise, the cell activity in roaches was different when turning clockwise from counterclockwise.

“The cells signaled which direction the animal just turned,” Varga said.

The greatest cell activity came while the white card was inserted in the wall, providing a visual landmark along with the cues provided by the passive motion from the rotating platform.

When the card was removed, the activity of some cells was the same at the same angles as the roaches rotated, indicating the insects knew their orientation without visual input.

To test this further, the researchers put a foil cover over the heads of a new set of cockroaches. As they rotated, the blinded roaches showed similar central complex activity to the earlier roaches that were turned without the landmark.

The researchers then removed the foil and inserted the card in the wall. As the roaches rotated, some central complex cells shifted their peak activity, suggesting the GPS was remapping by including the new visual information.

Some cells, however, showed no change in peak activity, indicating they rely only on the internal cues that were provided by the passive motion as they rotated.

When the researchers closely examined the activity of central complex cells, they found that some neurons appear to encode head direction like a compass, while others appeared to encode the relative direction of the rotation (clockwise or counterclockwise) after each stop, storing navigational context. And a small subset did both.

The upshot

“The fact we found these cell activities that are very similar to those in mice and rats and us strongly indicates insects rely on the same sensory inputs we need to orient ourselves and their brains process these inputs in a similar manner,” Varga said.

Ritzmann said either humans and cockroaches have a common ancestor, and this capability was retained or, more likely, represents convergent evolution.

“We argue that there are relatively few right solutions, that physics drives evolution and, ultimately, we get a very similar solution,” he said. “Each animal has receptors that take in critical information in order to navigate a complex environment.”

He predicts that almost all animals, from arthropods to humans, have similarly structured navigation systems that became more specialized and sophisticated in some species

Varga and Ritzmann are now designing experiments to learn more about the GPS, including whether roaches have a version of place and grid cells. Because they can focus on individual cells instead of areas of the brain, they may be able to directly see such things as which neuromodulators and hormones contribute to the process of orienting–which may be applicable to other animals, including people.

Source: Case Western Reserve University

Research Reference:

- Adrienn G. Varga et al. Cellular Basis of Head Direction and Contextual Cues in the Insect Brain. Current Biology, July 2016 DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.037