The Roman poet Lucretius’ epic work “De rerum natura,” or “On the Nature of Things,” is the oldest surviving scientific treatise written in Latin. Composed around 55 B.C.E., the text is a lengthy piece of contrarianism. Lucreutius was in the Epicurean school of philosophy: He wanted an account of the world rooted in earthly matter, rather than explanations based on the Gods and religion.

Among other things, Lucretius believed in atomism, the idea that the world and cosmos consisted of minute pieces of matter, rather than four essential elements. To explain this point, Lucretius asked readers to think of bits of matter as being like letters of the alphabet. Indeed, both atoms and letters are called “elementa” in Latin—probably derived from the grouping of L,M, and N in the alphabet.

To learn these elements of writing, students would copy out tables of letters and syllables, which Lucretius thought also served as a model for understanding the world, since matter and letters could be rearranged in parallel ways. For instance, Lucretius wrote, wood could be turned into fire by adding a little heat, while the word for wood, “lingum,” could be turned into the world for fire, “ignes,” by altering a few letters.

Students taking this analogy to heart would thus learn “the combinatory potential of nature and language,” says Stephanie Frampton, an associate professor of literature at MIT, in a new book on writing in the Roman world.

Moreover, Frampton emphasizes, the fact that students were learning all this specifically through writing exercises is a significant and underappreciated point in our understanding of ancient Rome: Writing, and the tools of writing, helped shape the Roman world.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

“Everyone says the ancients are really into spoken and performed poetry, and don’t care about the written word,” Frampton says. “But look at Lucretius, who’s the first person writing a scientific text in Latin—the way that he explains his scientific insight is through this metaphor founded upon the written word.”

Frampton explores this and other connections between writing and Roman society in her new work, “Empire of Letters,” published last week by Oxford University Press.

The book is a history of technology itself, as Frampton examines the particulars of Roman books—which often existed as scrolls back then—and their evolution over time. But a central focus of the work is how those technologies influenced how the Romans “thought about thought,” as she says.

Moreover, as Frampton notes, she is studying the history of Romans as “literate creatures,” which means studying the tools of writing used not just in completed works, but in education, too. The letter tables detailed by Lucretius are just one example of this. Romans also learned to read and write using wax tablets that they could wipe clean after exercises.

The need to wipe such tablets clean drove the Roman emphasis on learning the art of memory—including the “memory palace” method, which uses visualized locations for items to remember them, and which is still around today. For this reason Cicero, among other Roman writers, called memory and writing “most similar, though in a different medium.”

As Frampton writes in the book, such tablets also produced “an intimate and complex relationship with memory” in the Roman world, and meant that “memory was a fundamental part of literary composition.”

Tablets also became a common Roman metaphor for how our brains work: They thought “the mind is like a wax tablet where you can write and erase and rewrite,” Frampton says. Understanding this kind of relationship between technology and the intellect, she thinks, helps us get that much closer to life as the Romans lived it.

“I think it’s analagous to early computing,” Frampton says. “The way we talk about the mind now is that it’s a computer. … We think about the computer in the same way that [intellectuals] in Rome were thinking about writing on wax tablets.”

As Frampton discusses in the book, she believes the Romans did produce a number of physical innovations to the typical scroll-based back of the classic world, including changes in layout, format, coloring pigments, and possibly even book covers and the materials used as scroll handles, including ivory.

“The Romans were engineers, that’s [one thing] they were famous for,” Frampton says. “They are quite interesting and innovative in material culture.”

Looking beyond “Empire of Letters” itself, Frampton will co-teach an MIT undergraduate course in 2019, “Making Books,” that looks at the history of the book and gets students to use old technologies to produce books as they were once made. While that course has previously focused on printing-press technology, Frampton will help students go back even further in time, to the days of the scroll and codex, if they wish. All these reading devices, after all, were important innovations in their day.

“I’m working on old media,” Frampton says, “But those old media were once new.”

Provided by:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

More information:

Stephanie Ann Frampton. Empire of Letters. Oxford University Press. global.oup.com/academic/produc … 5407?cc=us&lang=en&#

Image:

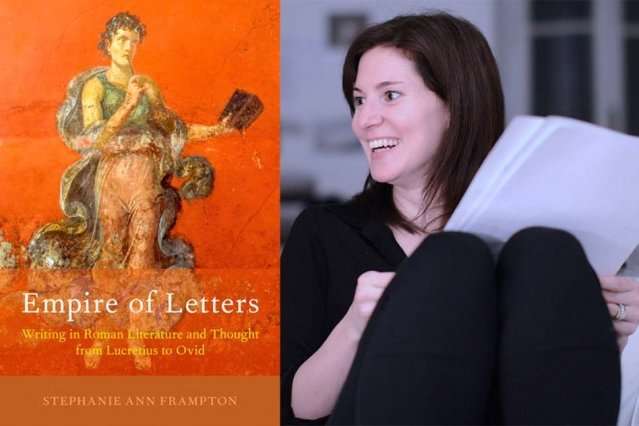

Stephanie Frampton, author of “Empire Letters.”

Credit: Catie Newell