New findings might help inform the design of more powerful MRI machines or robust quantum computers.

MIT physicists have observed signs of a rare type of superconductivity in a material called magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene. In a study appearing in Nature, the researchers report that the material exhibits superconductivity at surprisingly high magnetic fields of up to 10 Tesla, which is three times higher than what the material is predicted to endure if it were a conventional superconductor.

The results strongly imply that magic-angle trilayer graphene, which was initially discovered by the same group, is a very rare type of superconductor, known as a “spin-triplet,” that is impervious to high magnetic fields. Such exotic superconductors could vastly improve technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging, which uses superconducting wires under a magnetic field to resonate with and image biological tissue. MRI machines are currently limited to magnet fields of 1 to 3 Tesla. If they could be built with spin-triplet superconductors, MRI could operate under higher magnetic fields to produce sharper, deeper images of the human body.

The new evidence of spin-triplet superconductivity in trilayer graphene could also help scientists design stronger superconductors for practical quantum computing.

“The value of this experiment is what it teaches us about fundamental superconductivity, about how materials can behave, so that with those lessons learned, we can try to design principles for other materials which would be easier to manufacture, that could perhaps give you better superconductivity,” says Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics at MIT.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

His co-authors on the paper include postdoc Yuan Cao and graduate student Jeong Min Park at MIT, and Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan.

Strange shift

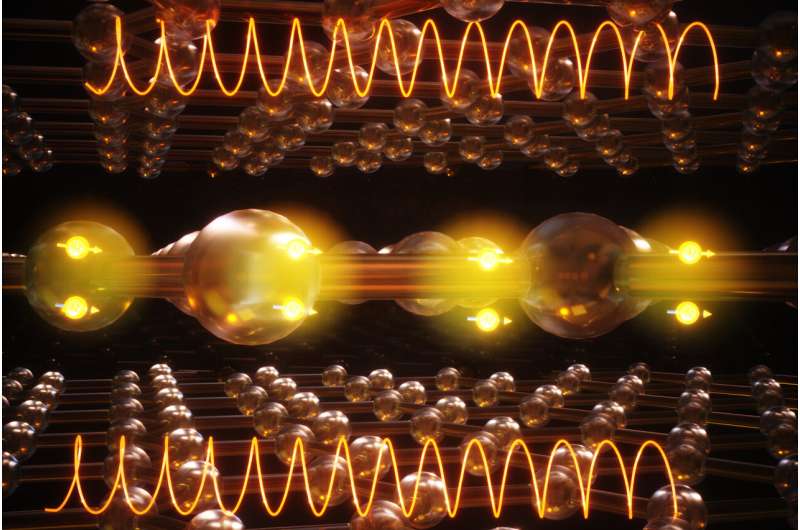

Superconducting materials are defined by their super-efficient ability to conduct electricity without losing energy. When exposed to an electric current, electrons in a superconductor couple up in “Cooper pairs” that then travel through the material without resistance, like passengers on an express train.

In a vast majority of superconductors, these passenger pairs have opposite spins, with one electron spinning up, and the other down—a configuration known as a “spin-singlet.” These pairs happily speed through a superconductor, except under high magnetic fields, which can shift the energy of each electron in opposite directions, pulling the pair apart. In this way, and through mechanisms, high magnetic fields can derail superconductivity in conventional spin-singlet superconductors.

“That’s the ultimate reason why in a large-enough magnetic field, superconductivity disappears,” Park says.

But there exists a handful of exotic superconductors that are impervious to magnetic fields, up to very large strengths. These materials superconduct through pairs of electrons with the same spin—a property known as “spin-triplet.” When exposed to high magnetic fields, the energy of both electrons in a Cooper pair shift in the same direction, in a way that they are not pulled apart but continue superconducting unperturbed, regardless of the magnetic field strength.

Jarillo-Herrero’s group was curious whether magic-angle trilayer graphene might harbor signs of this more unusual spin-triplet superconductivity. The team has produced pioneering work in the study of graphene moiré structures—layers of atom-thin carbon lattices that, when stacked at specific angles, can give rise to surprising electronic behaviors.

The researchers initially reported such curious properties in two angled sheets of graphene, which they dubbed magic-angle bilayer graphene. They soon followed up with tests of trilayer graphene, a sandwich configuration of three graphene sheets that turned out to be even stronger than its bilayer counterpart, retaining superconductivity at higher temperatures. When the researchers applied a modest magnetic field, they noticed that trilayer graphene was able to superconduct at field strengths that would destroy superconductivity in bilayer graphene.

“We thought, this is something very strange,” Jarillo-Herrero says.

A super comeback

In their new study, the physicists tested trilayer graphene’s superconductivity under increasingly higher magnetic fields. They fabricated the material by peeling away atom-thin layers of carbon from a block of graphite, stacking three layers together, and rotating the middle one by 1.56 degrees with respect to the outer layers. They attached an electrode to either end of the material to run a current through and measure any energy lost in the process. Then they turned on a large magnet in the lab, with a field which they oriented parallel to the material.

As they increased the magnetic field around trilayer graphene, they observed that superconductivity held strong up to a point before disappearing, but then curiously reappeared at higher field strengths—a comeback that is highly unusual and not known to occur in conventional spin-singlet superconductors.

“In spin-singlet superconductors, if you kill superconductivity, it never comes back—it’s gone for good,” Cao says. “Here, it reappeared again. So this definitely says this material is not spin-singlet.”

They also observed that after “re-entry,” superconductivity persisted up to 10 Tesla, the maximum field strength that the lab’s magnet could produce. This is about three times higher than what the superconductor should withstand if it were a conventional spin-singlet, according to Pauli’s limit, a theory that predicts the maximum magnetic field at which a material can retain superconductivity.

Trilayer graphene’s reappearance of superconductivity, paired with its persistence at higher magnetic fields than predicted, rules out the possibility that the material is a run-of-the-mill superconductor. Instead, it is likely a very rare type, possibly a spin-triplet, hosting Cooper pairs that speed through the material, impervious to high magnetic fields. The team plans to drill down on the material to confirm its exact spin state, which could help to inform the design of more powerful MRI machines, and also more robust quantum computers.

“Regular quantum computing is super fragile,” Jarillo-Herrero says. “You look at it and, poof, it disappears. About 20 years ago, theorists proposed a type of topological superconductivity that, if realized in any material, could [enable] a quantum computer where states responsible for computation are very robust. That would give infinite more power to do computing. The key ingredient to realize that would be spin-triplet superconductors, of a certain type. We have no idea if our type is of that type. But even if it’s not, this could make it easier to put trilayer graphene with other materials to engineer that kind of superconductivity. That could be a major breakthrough. But it’s still super early.”