The artificial cells could be used to sense changes in the body and respond by releasing drug molecules, or to sense and remove harmful metals in the environment.

Responding to chemical changes is a crucial function of biological cells. For example, cells can respond to chemicals by creating certain proteins, boosting energy production, or self-destructing. Chemicals are also used by cells to communicate with each other and coordinate a response or send a signal, such as a pain impulse.

However, in natural cells these chemical responses can be very complex, involving multiple steps. This makes them difficult to engineer, for example if researchers wanted to make natural cells produce something useful, like a drug molecule.

Instead, the Imperial researchers are creating artificial cells that mimic these chemical responses in a much simpler way, allowing them to be more easily engineered.

Now, the team have created the first artificial cells that can sense and respond to an external chemical signal through activation of an artificial signalling pathway. They created cells that sense calcium ions and respond by fluorescing (glowing). Their results are published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

First author James Hindley, from the Department of Chemistry at Imperial, said: “These systems could be developed for use across biotechnology. For example, we could envisage creating artificial cells that can sense cancer markers and synthesise a drug within the body, or artificial cells that can sense dangerous heavy metals in the environment and release selective sponges to clean them up.”

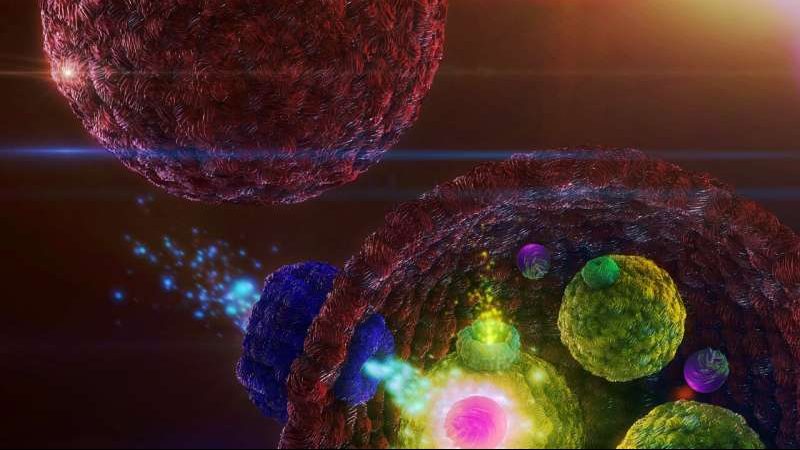

The team created an artificial cell that has smaller cells (‘vesicles’) inside. The edge of the cell is formed of a membrane that contains pores, which allow calcium ions to enter. Inside the cell, the calcium ions activate enzymes that cause the vesicles to release particles that fluoresce.

James added: “Biology has evolved to be robust by using complex metabolic and regulatory networks. This can make editing cells difficult, as many existing chemical response pathways are extremely complicated to copy or engineer.

“Instead, we created a truncated version of a pathway found in nature, using artificial cells and elements from different natural systems to make a shorter, more efficient pathway that produces the same results.”

The researchers’ system is simpler because it doesn’t need to account for many of the things cells need to get around in natural systems—such as by-products that are toxic to the cell.

Within the system, the membrane pores and the enzymes activated by calcium are from existing biological systems—the enzyme is taken from bee venom for example—but they would not be found in the same environment in nature.

The researchers say this is the strength of using artificial cells to create chemical responses—they can more easily mix elements found apart in nature than they can add an external element into an existing biological system.

Provided by: Imperial College London

More information: J. W. Hindley et al. Building a synthetic mechanosensitive signaling pathway in compartmentalised artificial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1903500116

Image: Building a synthetic pathway.

Credit: Imperial College London