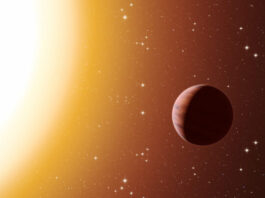

That round-the-globe rolling also explains how some grooves are superposed on top of others. The models show that grooves laid down right after the impact were crossed minutes to hours later by boulders completing their global journeys. In some cases, those globetrotting boulders rolled all the back to where they started—Stickney crater. That explains why Stickney itself has grooves.

Then there’s the dead spot where there are no grooves at all. That area turns out to be a fairly low-elevation area on Phobos surrounded by a higher-elevation lip, Ramsley says. The simulations showed that boulders hit that lip and take a flying leap over the dead spot, before coming down again on the other side.

“It’s like a ski jump,” Ramsley said. “The boulders keep going but suddenly there’s no ground under them. They end up doing this suborbital flight over this zone.”

All told, Ramsley says, the models answer some key questions about how ejecta from Stickney could have been responsible for Phobos’ complicated groove patterns.

“We think this makes a pretty strong case that it was this rolling boulder model accounts for most if not all the grooves on Phobos,” Ramsley said.

Provided by:

Brown University

More information:

Kenneth R. Ramsley et al. Origin of Phobos grooves: Testing the Stickney Crater ejecta model. Planetary and Space Science (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.pss.2018.11.004

Image:

Researchers used computer models to simulate the path of ejecta from Stickney crater on Mars’ moon Phobos. The simulations show how boulders take a flying leap over one particular area of Phobos, explaining why it’s devoid of grooves.

Credit: Ken Ramsley / Brown University