An international team of researchers used an X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory to create the first detailed maps of two melatonin receptors that tell our bodies when to go to sleep or wake up and guide other biological processes. A better understanding of how they work could enable researchers to design better drugs to combat sleep disorders, cancer and Type 2 diabetes. Their findings were published in two papers today in Nature.

The team, led by the University of Southern California, used X-rays from SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to map the receptors, MT1 and MT2, bound to four different compounds that activate the receptors: an insomnia drug, a drug that mixes melatonin with the antidepressant serotonin, and two melatonin analogs.

They discovered that both melatonin receptors contain narrow channelsembedded in the fatty membranes of the cells in our bodies. These channels only allow melatonin—which can exist in both water and fat—to pass through, blocking serotonin, which has a similar structure but is only happy in watery environments. They also uncovered how some much larger compounds may only target MT1 and not MT2, despite the structural similarities between the two receptors. This should inform the design of drugs that selectively target MT1, which so far has been challenging.

“These receptors perform immensely important functions in the human body and are major drug targets of high interest to the pharmaceutical industry,” said Linda Johansson, a postdoctoral scholar at USC who led the structural work on MT2. “Through this work we were able to obtain a highly detailed understanding of how melatonin is able to bind to these receptors.”

Time for bed

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

People do it, birds do it, fish do it. Almost all living beings in the animal kingdom sleep, and for good reason.

“It’s critical for the brain to take rest and process and store memories that we have accumulated during the day,” said co-author Alex Batyuk, a scientist at SLAC. “Melatonin is the hormone that regulates our sleep-wake cycles. When there’s light, the production of melatonin is inhibited, but when darkness comes that’s the signal for our brains to go to sleep.”

Melatonin receptors belong to a group of membrane receptors called G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) which regulate almost all the physiological and sensory processes in the human body. MT1 and MT2 are found in many places throughout the body, including the brain, retina, cardiovascular system, liver, kidney, spleen and intestine..

These receptors oversee our clock genes, the timekeepers of the body’s internal clock, or circadian rhythm. In a perfect world, our internal clocks would sync up with the rising and setting of the sun. But when people travel across time zones, work overnight shifts or spend too much time in front of screens or other artificial sources of blue light, these timekeepers are thrown out of whack.

Controlling the rhythm

When our circadian rhythms are disrupted, it can lead to psychiatric, metabolic, oncological and many other conditions. MT1 in particular plays an important role in controlling these rhythms but designing drugs that can selectively target this receptor has proven difficult. Many people take over-the-counter melatonin supplements to combat sleep issues or shift their circadian rhythms, but the effects of these drugs often wear off within hours.

By cracking the blueprints of these receptors and mapping how ligands bind to and activate them, the researchers lit the way for others to design drugs that are safer, more effective and capable of selectively targeting each receptor.

“Since the discovery of melatonin 60 years ago, there have been many landmark discoveries that led to this moment,” said Margarita L. Dubocovich, a SUNY distinguished professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University at Buffalo who pioneered the identification of functional melatonin receptors in the early 80s and provided an outside perspective on this research. “Despite remarkable progress, discovery of selective MT1 drugs has remained elusive for my team and researchers around the world. The elucidation of the crystal structures for the MT1 and MT2 receptors opens up an exciting new chapter for the development of drugs to treat sleep or circadian rhythm disorders known to cause psychiatric, metabolic, oncological and many other conditions.”

Harvesting crystals

To map biomolecules like proteins, researchers often use a method called X-ray crystallography, scattering X-rays off of crystallized versions of these proteins and using the patterns this creates to obtain a three-dimensional structure. Until now, the challenge with mapping MT1, MT2 and similar receptors was how difficult it was to grow large enough crystals to obtain high-resolution structures.

“With these melatonin receptors, we really had to go the extra mile,” said Benjamin Stauch, who led the structural work on MT1. “Many people had tried to crystallize them without success, so we had to be a little bit inventive.”

A key piece of this research was the unique method the researchers used to grow their crystals and to collect X-ray diffraction data from them. For this research, the team expressed these receptors in insect cells and extracted them by using detergent. They mutated these receptors to stabilize them, enabling crystallization. After purifying the receptors, they placed them in a membrane-like gel, which supports crystal growth directly from the membrane environment. After obtaining microcrystals suspended in this gel, they used a special injector to create a narrow stream of crystals that they zapped with X-rays from LCLS.

“Because of the tiny crystal size, this work could only be done at LCLS,” said Vadim Cherezov, a USC professor who supervised both studies. “Such small crystals do not diffract well at synchrotron sources as they quickly suffer from radiation damage. X-ray lasers can overcome the radiation damage problem through the ‘diffraction-before-destruction’ principle.”

The researchers collected hundreds of thousands of images of the scattered X-rays to figure out the three-dimensional structure of these receptors. They also tested effects of dozens of mutations to deepen their understanding of how the receptors work.

In addition to discovering tiny, gatekeeping melatonin channels in the receptors, the researchers were able to map Type 2 diabetes-associated mutations onto the MT2 receptor, for the first time seeing the exact location of these mutations in the receptor.

Laying the groundwork

In these experiments, the researchers only looked at compounds that activate the receptors, known as agonists. To follow up, they hope to map the receptors bound to antagonists, which block the receptors. They also hope to use their techniques to investigate other GPCR receptors in the body.

“As a structural biologist, it was exciting to see the structure of these receptors for the first time and analyze them to understand how these receptors selectively recognize their signaling molecules,” Cherezov said. “We’ve known about them for decades but until now no one could say how they actually look. Now we can analyze them to understand how they recognize specific molecules, which we hope lays the groundwork for better, more effective drugs.”

Provided by: SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

More information: Linda C. Johansson et al. XFEL structures of the human MT2 melatonin receptor reveal the basis of subtype selectivity. Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1144-0

Benjamin Stauch et al. Structural basis for ligand recognition at the human MT1 melatonin receptor. Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1141-3

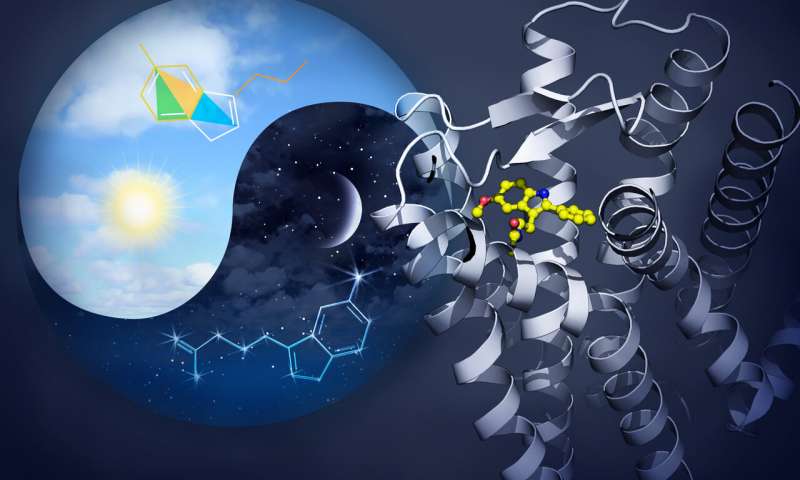

Image: The sleep-promoting hormone melatonin (shown as a constellation in the night sky) is synthesized from serotonin (shown as a kite) during night time, and both of these archaic molecules predate animal evolution. High melatonin levels at night permit it to establish its sleep-promoting properties by acting through high affinity receptors, depicted in the right side of the image composition.

Credit: Yekaterina Kadyshevskaya, Bridge Institute at USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience.