Scientists have successfully sequenced the genome of an extinct cave bear using a 360,000-year-old bone—the oldest genome of any organism from a non-permafrost environment.

The work, involving Nottingham Trent University and the University of Potsdam in Germany, has revealed a new evolutionary history for the giant cave bear, which became extinct about 25,000 years ago.

As part of the study, the team found that cave bears and their living relatives—the brown bear and polar bear—diverged from a common ancestor about 1.5 million years ago.

They also found that many significant events in bear evolution may have been driven by major global climate change about one million years ago, when cold phases—or ice ages—became longer and more intense and warm phases much shorter.

Cave bears, which grew larger than brown bears, weighing up to a ton, were widespread across Eurasia during the Pleistocene. They coexisted with brown bears and interbred with them, and modern brown bears still carry traces of extinct cave bear in their genomes.

Find your dream job in the space industry. Check our Space Job Board »

The sample analyzed by the researchers was from a cave bear which inhabited the Southern Caucasus, in what is now Georgia, around the Middle Pleistocene.

The oldest DNA sequences have previously come from permafrost environments where DNA is much better preserved.

For this study, however, the researchers wanted to push back the time limit of paleogenome sequencing much further into warmer, temperate zones, which were home to a far greater range of species.

The work involved extracting the ancient DNA from a tiny piece of petrous bone (0.05g) part of the skull that contains the organs of the inner ear and which is known to be resistant to contamination from external DNA sources.

The DNA was then prepared for sequencing, producing billions of individual short DNA sequences which represented a mixture of DNA from the cave bear and contaminants the bone had picked up over hundreds of thousands of years.

Computational analysis was used to sort the target sequences from the contamination, which is done my matching the short sequences to a reference genome of a related organism, in this case the polar bear.

In order to learn more about the evolution of the cave bear, once the team had the genome data for the 360,000 year old bear, they were able to compare with others from between 35,000 and 70,000 years ago to provide broad sampling of all the major cave bear lineages.

Because the time difference between the cave bear samples was so great, the team was able to count how many DNA mutations had occurred during this period.

From here they could calculate the rate of DNA mutation in the cave bear genome, as well as the time that the different lineages diverged.

Using the newly calculated mutation rate, the researchers found that cave bears and their living relatives, the brown and polar bears, diverged from a common ancestor.

And while they had previously shown that cave bears interbred with brown bears, with the mutation rate they are now able to date these events.

The study has further revealed the importance of climatic changes on species evolution, showing that bear evolution—the divergence of brown and polar bears, the divergence of cave bear lineages and the end of the gene flow between cave and brown bears—all occurred at around the same period a million years ago, when the world became colder.

While this study involved analyzing nuclear DNA, which is inherited from both parents, previous work has relied on mitochondrial DNA, which can only trace maternal ancestry. The team found that cave bears exchanged mitochondrial DNA frequently during their evolution, which until now had obscured their true evolutionary relationships.

“Our analysis of the whole genome data has revealed a new evolutionary history for cave bears,” said lead researcher Dr. Axel Barlow, an expert in palaeogenomics and molecular bioscience in Nottingham Trent University’s School of Science and Technology, who worked on the project with senior author Professor Michael Hofreiter at the University of Potsdam.

He said: “We have been able to determine the mutation rate of the cave bear genome for the first time. Using this information, we have discovered that major climatic changes may have been a factor driving major evolutionary events in these giant bears.”

“With DNA, we can decipher the genetic code of extinct animals long after they’ve gone, but over thousands of years, the DNA present in ancient samples slowly disappears, creating a time limit of how far back in time you can normally go.”

“Our study shows that this amazing molecule can survive even longer than previously thought, opening up new opportunities for genetic investigation over previously unimaginable timescales. We analyzed a petrous bone that was around seven times older than any we had previously studied, showing that genome data can be recovered from temperate zone samples spanning more than 300 millennia.”

“To put this in context, this cave bear probably lived before our own species, Homo sapiens, even came into existence.”

Unlike the brown bear, cave bears were vegetarian. Their name comes from the fact they used to hibernate in caves during the winter, a time when many died because they had failed to fatten up sufficiently.

The cause of their extinction is uncertain. It is thought that climate change could have been a factor, along with the influx of modern humans from Africa, which coincides with their decline. Cave bear bones have been found with human spear points embedded in them and early humans also painted images of cave bears on the walls of their caves.

The work is published in the journal Current Biology.

Provided by: Nottingham Trent University

More information: Axel Barlow et al. Middle Pleistocene genome calibrates a revised evolutionary history of extinct cave bears. Current Biology (2021). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.073

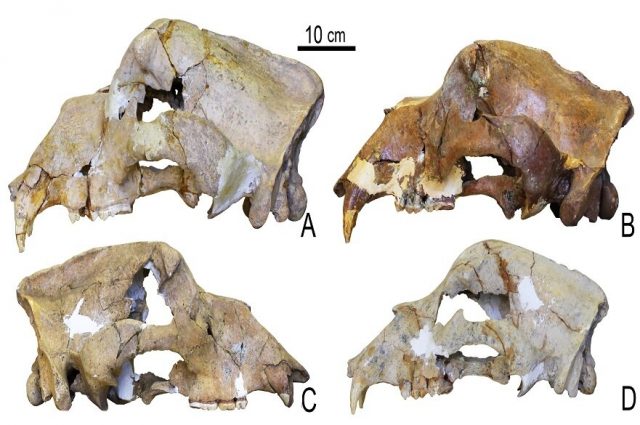

Image: Cave bear skulls from the Kudaro Caves in the Caucasus mountains, including (D) from the Middle Pleistocene.

Credit: Gennady Baryshnikov